T. rex fossil found by boys during hiking in North Dakota

6/10 (UPI)3A3-year-old boy who went hikingin North Dakota noticed something sticking out ofthe ground and wasshocked to learn that he had discovered a fossil of a Tyrannosaurus Rex.

Jessin and Liam Fisher, 10 and 7, were hiking theNorth Dakota Bureau of Land Management land in Badlands, near Marmers, with their cousin Kayden Madsen, 9, and their fatherSam Fisher.

They askedTyler Lyson, ahigh school classmate of Sam Fisher and now acuratorof paleonto logyatthe Denver Museum of Natural Sciences, to help identify what they found during their 2022 hike.

Lyson and his paleontology team accompanied the family on a return journey to the discovery sitein the summer of 2023,determined that the boys had discovered the juvenile tyrannosaurus fossil. The fossil will be shownat the“Discovering Teen Rex” exhibition at the Denver Museum of Natural Science, which willopenon 6/21.

“By going outand embracing their passionand the thrill of discovery, these boys have made incredible dinosaur discoveriesthat advancescience and deepentheir understanding of the natural world,” Lyson said in a news release. “I’m excited to delveinto the “Teen Rex Discovery“experience, which I think museum guests will inspire imagination and wondernot only inour community, but around the world!”“Atthe opening of the exhibition,thepremiereof Documentary Twillalsoappear. Rexrecordedthe discovery of fossils, “T.It features “Anunprecedented journey into the world of Rexand hisfellow Cretaceous carnivores.”

Learn more: https://www.adventurefilm.academy/

Weekend Warm-Up: Alone Across the Canadian North by Canoe

Photo: Screenshot

An overhead view of the Hudson Bay Lowlands. Complex! Photo: Screenshot

The Hudson Bay Lowlands in green. Map: Wikimedia Commons

Navigating whitewater. Photo: Screenshot

Portage hell, horsefly heaven

It’s hard to believe, but this is a shot of a canoe portage. Looks fun, huh? Photo: Screenshot

Bloodsuckers and biters. Photo: Screenshot

Photo: Screenshot

Balsam balm

Shoalts’ balsam fir sap treatment sealed his wrist wound perfectly. Photo: Screenshot

Source: https://explorersweb.com/weekend-warmup-canoe-hudson-bay-lowlands/

Learn more: https://www.adventurefilm.academy/

Pakistanis Take to the Slopes in ‘A Journey About Sharing’

Shred the gnar. Photo: Screenshot

Children in one of Pakistan’s isolated valleys enjoy downhill snowsports over their long winter break. Photo: Screenshot

Skinning up is hard without skins

Riding in Pakistan. Not bad! Photo: Screenshot

Having the right gear makes everything more fun. Photo: Screenshot

A meandering journey

Hard to beat these turns. Photo: Screenshot

Source: https://explorersweb.com/weekend-warmup-a-journey-about-sharing/

Learn more: https://www.adventurefilm.academy/

FKT Runners to Attempt Lhotse This Weekend

Chris Fisher, left, and Tyler Andrews on top of Chukkung Ri. Photo: Andrews/Fisher

Added challenges

Source: https://explorersweb.com/fkt-lhotse-makalu/

Learn more: https://www.adventurefilm.academy/

Beyond Everest: Hiking the Himalaya

From the terai to the mountains

Yaks move through fresh snowfall in the village of Machermo. Photo: Martin Walsh

Cheerful chaos

Dawn light hits a peak near Namche Bazaar. Photo: Martin Walsh

Lukla and the route to Everest

The Dhudh Kosi. Photo: Martin Walsh

100kg packs

Local porters move loads toward Namche Bazaar. Photo: Martin Walsh

The village of Dole, with Phortse visible beneath Kantega (6,782m) down the valley. Photo: Martin Walsh

Acclimatizing and inching higher

A Himalayan Monal, Nepal’s national bird, struts its stuff near Namche Bazaar. Photo: Martin Walsh

Himalayan tahr. Photo: Martin Walsh

In the shadow of Cho Oyu

Source: https://explorersweb.com/beyond-everest-hiking-the-himalaya/

Learn more: https://www.adventurefilm.academy/

SKI BUM CULTURE HITS REALITY

Nearly two decades ago, I moved to the mountains to be a ski bum, chasing snow. I was a stereotype—an East Coast kid pulled west by the promise of bigger adventures and higher mountain ranges. I was also part of a counterculture that rejected social norms in favor of 100-day ski seasons.

In ski towns in western Colorado in 2005, risk was everywhere, but in a way that felt exciting. I liked the brag of drinking too much, and I was too naïve to notice harder drugs. Climate change seemed theoretical, and no one I knew had died in the mountains yet.

Corporate entities were just starting to binge-buy resorts while I somehow thought that living in my car was cool and I could exist like that forever.

But myths are complicated things to keep alive, and I eventually left ski towns to work as a writer, already seeing the ski-bum dream changing. I saw friends struggling to build careers, families and community while still chasing the fragile dream that a powder day topped almost everything.

So recently, I went back to see what was going on, to try to track the evolution of what had been my own obsession. I looped through mountain towns across the West, from Aspen, Colorado to Victor, Idaho and Big Sky, Montana, to assess the current state of ski bums.

What I found was that everyone trying to build a life in those towns was struggling, from my old colleagues who had stuck around and wished they’d bought real estate to “lifties” fresh out of school.

“A lot of people here are living a fantasy I can’t obtain,” said Malachi Artice, a 20-something skier working multiple jobs in Jackson, Wyoming.

At the most basic level, the math just didn’t work. In most mountain towns, it’s now nearly impossible to work a single full-time service job, the kind that resort towns depend on, and afford rent. The pressure shows up in nearly everything, including abysmal mental health outcomes like anxiety and depression.

Ski towns have some of the highest suicide rates in the country, and social services haven’t expanded to meet demand. Racial gaps are also widening in an industry that often depends on undocumented immigrants to fill the poorly paid, but necessary, jobs it takes to keep a tourist town running.

On top of all that, abundant snowfall, the basis of a ski resort’s economy, is getting cooked by climate change.

And sure, you can argue skiing is superficial and unimportant, but ski towns—some of the most elite and economically unequal places in the country—are microcosms for the way our social fabric is splitting.

Ski towns face crucial, complicated questions: Can they build affordable housing and also preserve open space? What happens when healthcare workers or teachers won’t take jobs because they can’t find a way to live in the community they serve? Will a town willingly curb growth when that’s what supports the tax base?

There are no easy answers because the problems are entrenched in both that slow-moving nostalgia that stymies change, and in the downhill rush of capitalism, which gives power to whoever pays the most: The housing market always tilts toward high-end real estate instead of modestly priced homes for essential workers.

What we value shapes our lives, and so I think we must hold the ski industry to higher standards. If these rarefied places can find ways to support working as well as leisure-based communities, they could serve as lessons for change elsewhere.

During my tour, I saw necessary workers in the ski industry facing hard economic choices, but I also saw positive, community-scale change. In Alta, Utah, for instance, the arts nonprofit Alta Community Enrichment added mental health support when its employees reported an urgent need.

If ski-resort towns are going to survive, the lives of their workers need to matter, and that means caring about them—from affordable housing to accessible mental health support.

By Heather Hansman

For more information and details : https://adventure-journal.com/blogs/news/ski-bum-culture-hits-reality

JOSEPH KITTINGER, THE MAN WHO DOVE TO EARTH

First, the indescribable view. Earth, many miles below, twinkling blue, whorls of white and grey clouds. Home is down there somewhere, familiar faces, too, but everything you find comfortable and safe is hidden beneath a blanket of impossible distance. No way to reach any of it but to jump. The silence of the stratosphere is stunning. Nothing but the sound of your own anxious breathing in a sealed helmet. Now, it’s time. Gather yourself, take a deep breath, a hard swallow to settle the void in the pit of your stomach, a last look down at the earth below, a turn of your head to wonder at the impossibly bright stars, a brief moment to appreciate the beautiful absurdity of it all. Then you step into the void.

Joseph Kittinger’s job for the US Air Force in the late 1950s was making that leap. During his career he set records for highest balloon flight, longest free fall, and fastest speed achieved by a human being under their own power (well, under gravity’s too). Kittinger also had a decorated career as a fighter pilot, retiring as a Colonel and earning the Distinguished Flying Cross.

“I said, ‘Lord, take care of me now.’” Kittinger later recalled. “That was the most fervent prayer I ever said in my life.”

When his records for jumping out of the stratosphere were finally broken in 2012 by Austrian madman Felix Baumgartner, Kittinger was right in Baumgartner’s ear during his jump, literally, as the mission’s supervisor directing things over the radio.

“Felix trusts me because I know what he’s going through,” Kittinger said at the time. “And I’m the only one who knows what he’s going through.”

Kittinger was the sort of person who has a flash of what they want their life to look like as a child, then seemingly without any second guessing or hesitation, realizes that dream. He was born in Tampa, Florida, in 1928. As a kid he saw a Ford Trimotor parked at a nearby airfield (the sorta plane Indiana Jones liked to jump from in films). It sparked a lifelong love of aviation, and was the first step on a ladder Kittinger eventually climbed 102,800 feet into the sky.

An Air Force pilot of experimental aircraft in the 1950s, Kittinger was recruited to take part in Operation Man High and Project Excelsior, a series of experiments that kicked off America’s nascent age of space exploration. The Air Force had no idea what the human body could tolerate when it came to acceleration, deceleration, exposure to the thin upper reaches of the atmosphere, or, crucially for Kittinger, what might happen to a pilot if they were forced out of an aircraft at the furthest fringes of the atmosphere.

Kittinger made 3 jumps over 10 months from 1959 to 1960. They went like this. He piloted helium-filled balloons to a predetermined altitude riding inside a pressurized gondola-like car. Once there, he’d jump from the gondola, free fall for a time, then a series of parachutes automatically opened. Kittinger’s first jump nearly killed him when he became tangled in the cords of his stabilizing chute immediately into his jump. He plunged nearly 66,000 feet until his primary chute opened at 10,000 feet.

Undeterred, Kittinger jumped again a month later, before making his record-setting plunge in August, 1960. Aboard the balloon craft Excelsior III, he rose to 102,800 feet, an altitude record in itself. Kittinger’s right glove malfunctioned during the ascent, painfully swelling his hand to twice its normal size. He prepared his body and mind for the jump.

“I said, ‘Lord, take care of me now.’” Kittinger later recalled. “That was the most fervent prayer I ever said in my life.”

He free fell for 4 minutes, 36 seconds. At that altitude, Kittinger was effectively in space, a vacuum. He reached terminal velocity after 20 seconds of acceleration, hitting 614 miles per hour.

Kittinger later told Florida Today:

“There’s no way you can visualize the speed. There’s nothing you can see to see how fast you’re going. You have no depth perception. If you’re in a car driving down the road and you close your eyes, you have no idea what your speed is. It’s the same thing if you’re free falling from space. There are no signposts. You know you are going very fast, but you don’t feel it. You don’t have a 614-mph wind blowing on you. I could only hear myself breathing in the helmet.”

That would be enough for most people, in terms of high-flying excitement. But it was just the beginning for Kittinger.

After his final jump and another high-altitude balloon flight, Kittinger entered active combat duty in the skies above Vietnam. He served three tours, was credited with the kill of a MiG-21, and was shot down near Hanoi in 1972. For 11 months, Kittinger was a POW at the infamous Hanoi Hilton, fiercely observing military discipline to keep himself sane. He retired from the Air Force as a colonel in 1978.

Joseph Kittinger next to the Excelsior gondola on June 2, 1957. Note the sign: “This is the highest step in the world.” Photo: US Air Force

Would you be surprised to learn Kittinger later became the first person to pilot a hot air balloon across the Atlantic? In 1984 he took off from Maine and drifted 3,543 miles over 3 days before alighting safely in Italy.

In his later years, he ran the Rosie O’Grady’s Flying Circus, in Orlando, Florida, taking people up in hot air balloon rides. Did his customers know the avuncular man at the controls had once leapt from a balloon at the fringes of space? Whether or not they did, they were in expert hands.

When Kittinger’s father watched his son at age 13 scale a 40-foot tree to pick coconuts, he was said to exclaim, “Everybody wants coconuts, but nobody has the guts to go up there and get them.”

Those guts earned Kittinger a Distinguished Flying Cross, high-altitude records that stood for 52 years, and the Smithsonian’s highest honor, the National Air and Space Museum Trophy. More importantly for Kittinger, who always pointed out his balloon trips as part of Operation Excelsior were not meant to break records, but to gather data, he experienced the kind of grand adventure only a handful of humans have ever known—charting a part of the Earth, or the envelope of it, nobody else had ever seen.

“Life is an adventure, and I’m an adventurer,” he told U.S. News and World Report in 1984. “You just have to go for it. That’s the American way.”

By Justin Housman

For more details and information : https://adventure-journal.com/blogs/news/joseph-kittinger-the-man-who-dove-to-earth

Living on Easy

A trip to Amami Ōshima, Japan, transports Gerry Lopez to a familiar feeling on a distant land.

I was born in Honolulu in the late 1940s, before Hawai‘i was a state. In those early days, the living was easy. It was called “island style,” and that was the way everyone lived … well, at least everyone we knew. The beach across from the zoo was where we spent afternoons after school and on weekends. There were tourists down near the hotels and at the Sunday lū‘au at Queen’s Surf, but otherwise, the rest of Waikīkī Beach and Kapi‘olani Park was mostly locals only. My mom took my brother and me surfing one day at Baby Queen’s, and none of us, Mom included, had any idea that life going forward would inexorably shift to another path. We’d both been bitten by the surf bug that day, but it was Victor who felt it first.

His school buddy, Stanford Chong, and his whole family surfed together, so before long, Vic had his own surfboard and was surfing with them all the time. They owned a country house on the beach on O‘ahu’s East Side between Crouching Lion and Chinaman’s Hat (Mokoli‘i), and often I’d be invited to spend the weekend there since Stanford’s sister, Marlene, and I were classmates.

They had a large house with a big yard and some sprawling hau trees around an outdoor barbecue and firepit. We would drive out from Honolulu town, over the Pali, through Kāne‘ohe town, along the windward side—the ocean on our right and majestic Ko‘olau Range on the left. The East Side gets rain almost daily, so everything is green and growing. In the morning, we’d walk the beach to find any Japanese glass floats that may have washed ashore, although the grown-ups always got the jump, waking earlier and knowing where to look. After breakfast, sometimes Mr. Chong would take the boat out with all the kids and fish a little or explore Chinaman’s Hat or spearfish the reefs in front of the house.

Somewhere along the line, and without even understanding it was happening, I developed a little boy’s affinity for this side of the island. It was like falling under a spell … there was its special feel, look, smell and idiosyncrasies. Like when the trade winds blew, I learned to be on the lookout for Portuguese man-of-war and so avoid its painful sting. Or noticing how vivid and bright the stars were on dark nights, without the town lights to spoil them.

I had no idea at the time, but later on, when older and looking back, I realized how idyllic that was—life at that young age is full of questions, uncertainty and finding oneself on shaky ground. But those times on the East Side were like putting aloe vera on a burn; there was a very distinct, soothing ahhh about it, and I looked forward to each time we got to go.

In a way, life is a little like Dad’s car … it takes us down the road, and at some point, a stop at the service station is needed to keep going. The weekends at the Chongs’ beach house were that gas-station stop. Then things changed. I began to run on another kind of fuel; surfing started to rear its head and fill my tank. I don’t think I even realized that one had replaced the other, or if replace was even what it did. Surfing, as the complete endeavor, inevitably takes not just some of one’s time—it takes it all. A deep passion develops, and while it’s all one wants to do, at the same time, it stokes a great fire down inside that drives a person to … well, to be insatiable for even more of it.

Perhaps that earliest harmony at the Chongs’ had something to do with it, but I found myself living in Kahalu‘u, way out on the East Side, and spending a lot of time in the car driving: either to town for my surf-shop business, Ala Moana for summertime surf or the long haul to the Country in the winter for the waves there. Sometimes if I was a passenger, I would look at the Chong house as we zoomed by. I never saw anyone; a couple of times I stopped, but it was empty and the sweet and tangy awareness that I used to have was no more. But surfing was keeping my gas tank full, so I guess I didn’t miss it.

Life happened and the years flew by. In 2017, the film crew at Patagonia suggested a documentary film project that must have been meant to be because it unfolded like a spinnaker sail does when a stiff wind blows—not that it was without a few wrinkles—but by spring last year we were ready to premiere it.

A tour ensued throughout the US, Europe, Australia and Japan. The director, Stacy Peralta, did most of the stops with me except for Japan. He was busy, so I went alone. In the undertaking of this assignment, we never thought that something like COVID-19 would have such an effect, but it surprised the entire world and certainly put up some hurdles for our movie tour. Japan had only just opened its doors to visitors when I got there. We had showings in Kamakura, Sendai, Tokyo, Osaka and Fukuoka: all cities where I had been before, with old friends in all of them, and the film showings went like clockwork.

The final stop was Amami Ōshima, one of the little islands near Okinawa that I’d heard about but never visited. The monkey wrench was that a typhoon with an unpredictable trajectory was aimed toward the same place we were bound for. For most people, a typhoon warning is usually a good reason to reschedule one’s trip. For a surfer, however, this is a sure sign of surf coming and serves as an attraction rather than a deterrent, and our entire Patagonia Japanese crew were surfers. Of course, we went.

As we flew into the airport, the ocean looked spectacular from above, deep blue with strong trade winds blowing whitecaps and swells toward the islands. Staring out the window, I was mind-surfing those waves on a downwind SUP or a wing foil.

We landed still in our city clothes, long pants, shoes. But all our friends in the terminal were waiting for us in shorts and slippers. Yeah, man, at a glance, I could tell they were all living on easy. I couldn’t wait to change clothes and join them. As soon as I walked out the plane’s door, something happened … a feeling, a smell, the green hills. I don’t know what it was, but I felt like I was back to some place I had been before. I looked more closely. The plants and trees were familiar, the ocean had a windswept look I recognized and waves were breaking in crystal-clear water over coral reefs, sandy beaches; it felt like I should know it even though I didn’t.

We were greeted with leis by some old friends and many new ones who had an easy, friendly, familial excitement. Driving in the car back to our host’s home and surf shop was eerily déjà vu, too. When we stopped, I quickly changed into my shorts and slippers and just that made me feel more at home in these surroundings.

A quick walk down to the beach to connect with the sand and the water, touching them and seeing the weathered siding on the homes that comes from living on a windward shore, gave me an astonishing revelation for the strong sensations I was having. I was back at the Chongs’ house on the East Side from 65 years ago—that loving feeling had never left. It just needed the right coaxing to come rushing back like it always had before. Good feelings are strange and powerful. We usually take them for granted as we revel in them, never thinking how deep they go or how long they’ll last. The rest of our trip was totally smooth and seamless, as one would expect with family and friends. We drove to the other side of the island. For me, the whole way looked and felt like Hawai‘i. We surfed excellent waves with dear friends, ate great food, talked story—life was very good.

The next day we showed the film to the local surf community. They were an awesome audience. That evening, with the hurricane hovering just over the horizon, we flew out, arriving late into Tokyo. The typhoon hit Okinawa, but maybe all the good vibes were strong enough to cause the storm to veer away from Amami Ōshima.

It was a wonderful trip, “island style” the entire way and one I won’t soon forget. I left the little island and its tight surf community with an absolutely full tank of premium-grade fuel. I’ll just bet that everyone else was topped off, too.

By Gerry Lopez

For more information and details : https://www.patagonia.com/stories/living-on-easy/story-141483.html

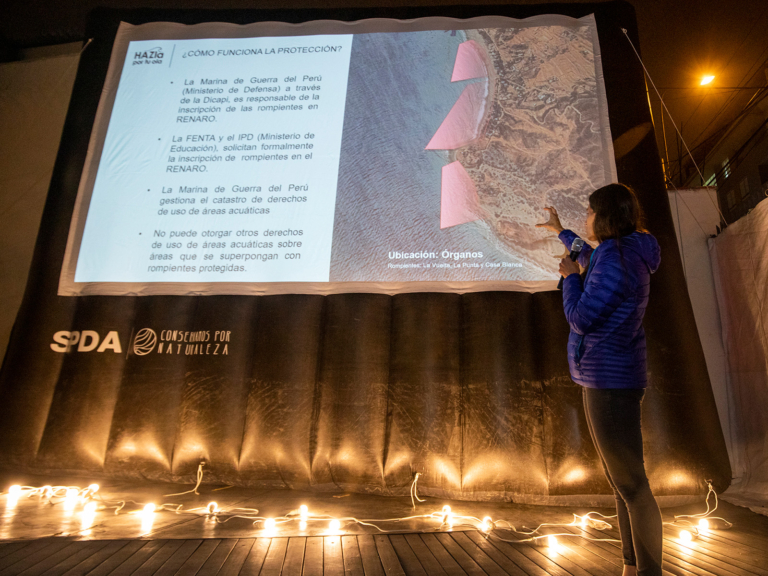

The Quest to Save 100 Waves in Peru

A friendship built between waves becomes a powerful alliance for the protection of surf breaks.

Carolina Butrich loves to read and hates mangoes. She uses Microsoft Excel for everything, including designing her house. She gives abundant affection but is claustrophobic and can’t handle hugs. Above all, Carolina is a flame that does not go out.

Although we went to the same school in Lima, Peru, we never met there. The first time I saw her was in the waters of the Cañete River in 2010. She showed up with her long hair dancing in the wind and tan smile lines, the kind that indicate a life spent near the sea. I was suffering to keep my kayak upright while she paddled for two hours straight with ease. We didn’t talk, and I didn’t ask her name. Years later we realized that was the first of many sessions together as our friendship built around protecting surf breaks and nature in our homeland bloomed—a task for which I could not have asked for a more ideal partner.

Peru is generally known for Machu Picchu, mysterious Nazca lines and its flavorful ceviches. What most don’t know is that the first law to create a legal system of protecting waves was born here. In the ’80s, the mayor of the Chorrillos district started the process to build a road that many say changed the ocean’s landscape dynamics and destroyed the now mythical La Herradura . Years later, when a poorly planned pier almost destroyed the perfect wave of Cabo Blanco, the surfers organized themselves. They formed a conservation association and left no stone unturned until the Peruvian Congress approved the Ley de Rompientes (Law of the Breakers) in 2000. It took 13 years for it to go into effect and became the legacy of a new generation of Peruvian surfers committed to saving waves. In 2016, Chicama, famous for being the world’s longest wave, was the first to be protected. Today, there are 43 protected waves in Peru thanks to thousands of people who’ve joined the Hazla por tu Ola campaign, an effort that fueled the surf community with purpose and welded my ironclad friendship with Carolina.

After we first met at the Cañete, I started a project called Conservamos por Naturaleza, an initiative of the Peruvian Society of Environmental Law that invites and facilitates anyone’s involvement in nature conservation. We promote a voluntary conservation movement because we believe that conservation must be ingrained in the culture of everyday society. Today, we have over 250 initiatives supported by families, communities and organizations that protect almost 500,000 acres of natural ecosystems in Peru.

While I dedicated myself to Conservamos por Naturaleza, Carolina traveled the world, with water being the sole constant in her life. She competed in windsurfing racing until she saw a video of legendary windsurfer André Paskowski riding waves at Ho‘okipa in Maui. She decided that within a year she would be riding those same waves. So, she started taking the bus nearly 400 miles (640 kilometers) north from Lima to Pacasmayo every weekend to learn how to ride waves while pursuing a degree in environmental engineering.

Soon, windsurfing Ho‘okipa became a reality, and just two years later she was competing against the best in the Professional Windsurfers Association world tour. Maui in Hawai‘i, Paracas and Pacasmayo in Peru, and Jericoacoara in Brazil became usual stops. At each location, Carolina found an extended family. Before finishing her degree, she got offered her dream job in Jericoacoara as the head windsurfing instructor at ClubVentos. Carolina didn’t want to miss the opportunity, though she did sign a contract with her mother, who helped her finance her studies, promising that she would return six months later to finish college.

That decision would alter the path of her life because in Brazil she met André Paskowski and they fell in love. André had a terminal illness, and they would only get a year together. But they were determined to make memories. Between therapies, they traveled to film the windsurfing documentary Below the Surface, which focuses on former Professional Windsurfers Association World Champion Victor Fernandez and his friends. André passed before finishing the documentary, but Carolina completed it. The process helped her get on her feet again. They had the goal of presenting it at a film festival in Sylt, Germany, and she knew that’s what André would have wanted. “We had everything to be happy together: love, trust, fun, common interests, respect, admiration, everything … except time,” Carolina wrote in a farewell letter.

We saw each other in 2013 at an environmental event, and I told her about Conservamos por Naturaleza. When she came back to Peru two years later, she visited our office and said that she had returned to, “give something back to the sea for everything it has given me.”

I told her that our organization was created precisely for people who wanted to generate a positive impact, and that her timing was spot-on since we were about to launch a campaign that would allow us to protect the waves of Peru. When I mentioned that we had no budget and needed to raise over $500,000 in the next 10 years while uniting a very dispersed Peruvian surfing community to protect 100 waves, Carolina asked, “When do we start?”

A few weeks later, we found ourselves in front of a crowded room to launch Hazla por tu Ola. Carolina, terrified of speaking in public, stuttered due to nerves but against all odds—and encouraged by a couple of pisco shots—explained that if we wanted to protect our waves, we had to be organized as a community and not rely on the government. Today, Carolina handles herself with ease when she gets on stage. A key part of our organization is to inspire citizens and private companies to take action for nature conservation. Her dedication and leadership toward this goal earned her the Carlos Ponce del Prado Award in 2019, and the Latin America Green Award for Hazla por tu Ola in 2020.

There are a few different approaches when it comes to protecting surf breaks. In countries with strong institutions and more mature ocean governance structures, surf-break protection usually falls under marine spatial planning regimes. These processes allow governmental agencies to navigate the different interests over a particular marine area and set the rules for its use. For instance, countries such as New Zealand and Australia have coastal management plans, where recreational uses are prioritized in wave zones and activities that may affect those zones are limited. In Australia, there’s even a surf management plan for the Gold Coast and millions of Aussie dollars are invested for its implementation.

But in many other countries, marine spatial planning is nonexistent and the communities that are committed to protecting marine ecosystems are in constant dispute with other stakeholders to make conservation a public priority. This is the case in Peru, where, for example, the Navy receives several requests to grant permits for the construction of ports, pipelines, piers, coastal defense structures and more.

The Law for the Protection of Surf Breaks created a formal process for citizens to put conservation before other potential uses. The way it works is if you can prove there’s a wave in a potential area of protection, you must submit a technical file and a map of the area to the Peruvian Navy. These documents need to show the existence of a wave and its physical features through a seabed analysis and a swell record. The Peruvian Navy then validates the information, and once the wave is registered in the National Registry of Surf Breaks, the government can no longer grant rights for activities that may affect the waves—meaning no new breakwaters, docks, piers, underwater pipelines and more. Basically, all construction that could affect the window and path of a wave are avoided.

Led by Carolina, Hazla por tu Ola identifies and works with community leaders to raise the funds needed to hire specialists. The specialists then prepare the files and follow up with the authorities so that the waves are registered and stay protected. It costs $3,000 to $6,000 USD to get the research done and submitted to the Navy for every single wave. To date, citizens in Peru have raised 90 percent of all funds needed for wave protection.

In 2018, we were invited to the Global Wave Conference organized by Save the Waves Coalition (SWC) in Santa Cruz, California. SWC played a key role supporting the local Peruvian community in the process to protect the iconic wave at Huanchaco, famous for its traditional caballitos de totora, an individual fishing boat woven out of reeds and used by the locals to fish for the past 3,000 years. The relationship with SWC has grown throughout the years and has been key in amplifying Hazla por tu Ola’s model in other countries, connecting us with activists across the world. Our most recent collaboration with them consists of an online platform with a systematization and comparison of legal tools and approaches for the protection of surf breaks, including case studies from 12 countries. We hope this information will help local leaders and politicians to commit to protect surf breaks all over the globe.

With momentum on our side, we’re determined to save as many waves as we can. “We have set the goal of having 100 waves protected by 2030,” said Carolina. “We are not going to stop until we have all the waves in Peru protected by law and there are more countries that apply this model.”

And it’s working. The Peruvian model is being adopted in Latin America. Caro has been working with grassroots activists in Ecuador who created a new collective called Mareas Vivas, which is ready to start a campaign to collect citizen signatures and present a law proposal to the Parliament for surf breaks protection. South of the border, in Chile, after a speech I gave about Hazla por tu Ola in 2016, Luis Felipe Rodríguez Besa—now also a close friend—got inspired and co-founded Fundación Rompientes along with the talented filmmaker Rodrigo Farias Moreno and lawyer Juan Esteban Buttazzoni. Fundación Rompientes has played a key role aligning the efforts of several groups for the protection of surf breaks in Chile, and we have been a natural ally since day one.

Recently, the Chilean Congress approved a bill promoted by Fundación Rompientes that seeks to protect Chilean surf breaks. The project is now to be evaluated by the Senate. Also, in Mexico, the community of Puerto Escondido has organized and set up a holistic plan for the sustainable development of their coastal area that includes fostering the creation of a local Ley de Rompientes. Both Save the Waves Coalition and Hazla por tu Ola are providing guidance in the process. When facing environmental challenges, it is easy to feel overwhelmed, so knowing that you can exchange ideas and relate to fellow activists doing the same in other countries is invaluable.

When Carolina returned to Peru in 2015, she thought it would be just for a few months. Lima had been a place from which she always found herself escaping. Eight years later, she’s still here because she has found balance. She has a job with purpose, is at the forefront of Hazla por tu Ola’s goal of protecting surf breaks and is surrounded by people who inspire her. She’s also allowed herself to fall in love again and is starting a family. Although she doesn’t try to, Carolina teaches us that living your life without taking anything for granted and setting down some roots—without necessarily anchoring yourself to one place—is key to achieving important changes because, as waves have shown us, there is no barrier that can resist what is done with love and perseverance.

By Bruno Monteferri

For more information and details : https://www.patagonia.com/stories/the-quest-to-save-100-waves-in-peru/story-146583.html

The Wave below the Sleeping Rabbit

Meet the man working to save Mexico’s Punta Conejo.

All photos by Ryan “Chachi” Craig

Uriel Camacho invented the sport of bodysurfing. At least, he thought he did.

This was before Salina Cruz, a town on the edge of the southern state of Oaxaca, Mexico, became an international surf destination. Before its sand-bottom pointbreaks would plaster magazines. Before the all-inclusive camps, 4×4 trucks and direct flights weighing heavy with board bags.

Camacho had no reference for wave riding of any kind 30 years ago. One day, he just kicked his way out to an empty wave and taught himself to swim. “Hola, hola, ¿cómo estás?” he shouted at the sea. “No me vayas a ahoga.” (“Hello, hello, how are you? Please don’t drown me.”)

“One day, I caught a wave,” he tells me, holding his arm straight in front of him. “I thought I was the first one to do it.”

Camacho, 44, now runs Luna Coral Soul Surf, a camp named after his two daughters. He is stocky, with a long, dark ponytail, sunbaked skin, a hook nose and deep smile lines—the result of spending nearly every day of the last 13 years as a surf guide under the brutal Oaxacan sun.

He recounts his bodysurfing story over mezcal at his dining room table. It’s dark, and I have just arrived from the airport. As soon as I get my luggage to my room, he demands that we take a shot, a celebration of the coming swell set to arrive in two days, the biggest of the summer. We clink, “¡salud!”

I met Camacho a month prior in Northern California. We both attended a summit organized by the Save The Waves Coalition—an environmental nonprofit that protects surf ecosystems. “Visit anytime,” he offered, surely not expecting that I would actually take him up on it.

Camacho’s surf camp is on the backside of Punta Conejo, a right pointbreak on the edge of a sand-covered mountain that resembles a sleeping rabbit. Directly inland from Punta Conejo are mangroves, a forest of thirsty trees and visible root systems that are home to a small industry of shrimp fishermen who cast their nets along the still, windless water.

Beyond the mangroves is the city of Salina Cruz. It’s a port town of more than 80,000 with a newly finished harbor for international shipping vessels, most transporting petroleum. Mexico’s President, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, is planning to expand the project. It will gut Punta Conejo, relocate Camacho and his family, along with four surrounding communities and a number of other surf camps in the Playa Brasil area, and dredge thousands of hectares of mangroves to stage excess petroleum ships.

Camacho has a mission to stop it.

He is working with Save The Waves, Wildcoast, Union de Surfistas y Salvavidas de Salina Cruz and more conservation groups to designate Punta Conejo and the nearby Punta Chivo and Escondida as protected areas.

Flattening Salina Cruz’s most consistent wave with a sea of cement would also send the shrimp industry belly-up and dredge the delicate ecosystems surrounding the break. Just north of Playa Brasil’s long stretch of beach, the new development would destroy the breeding and hatching ground of the vulnerable leatherback and olive ridley sea turtles native to the area.

Unfortunately, Mexico has a history of ruining world-class surf spots. In the 1970s, a beachbreak version of O‘ahu’s Pipeline called Petacalco, which would have banked hundreds of millions in surf tourism dollars over the years, was destroyed. As Gerald Saunders wrote in The Surfer’s Journal: “Thanks to the underwater canyon to the south and the damming and jetty construction on the Rio Balsas a few miles to the north, there was no way the sandbars could be replenished as rapidly as the surging swell washed them away. What might have taken several more years was done literally overnight. Petacalco was gone.”

On June 2, 2024, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador is up for reelection. This means he could try to hastily move the Punta Conejo project forward before designation can be set. Hopefully, he recognizes the injustice of the project and the activists persuade him to see the wave as a valuable tourist attraction better left alone.

“Están locos,” Camacho says as he shakes his head after bringing me up to speed on the issue.

The next morning, we pack our boards into Camacho’s black, salt-rusted SUV and drive to Punta Conejo, 10 minutes away. We bump along a dirt road, passing goats, burning trash and cacti with barbs big enough to impale a man. He shifts into four-wheel drive, and we skid along the sand to the point.

Five other trucks are already there, and surfers stand around in tank tops and boardshorts while small waves yawn down the point. It’s a shame, as part of the reason I’m down here is to report on the proposed port at the “world-class” Punta Conejo.

“No sand,” Camacho says, turning to me. It’s September, the end of the popular surf season for Oaxaca, and south wind has eroded the sandbar at Conejo. We watch a while longer and decide to check the next spot a few miles north: Punta Chivo, named because the rock at the end of the point looks like a goat.

Chivo is better. At least the pros make it look better. Their filmers hide under canopies next to the trucks capturing every wave in high definition. And the lineup of surf guides know that at 10 a.m. guests will get thirsty, so they stock coolers with water, electrolytes and beer. Today, the surf camps have their program dialed. As I wax my board for the first session, the efficiency of the whole experience is not lost on me.

Though this pampered scene isn’t the rugged bushwhacking of Gerry Lopez in the ’70s, these crowds may be the not-so-secret weapon to stopping the port expansion. The number of flights into Salina Cruz’s main airport, Bahías de Huatulco, has nearly quadrupled since 1997, from 123,000 per year to 452,000 per year. If the international surf community makes enough noise, and the Mexican government begins to see these waves as the multimillion-dollar cash registers that they are, they could halt the development.

After we surf Chivo for a few hours, Camacho and I sit in beach chairs and I crack a cold beer—it’s 10 a.m. and seems like the right thing to do. As I sip, Camacho tells me about Salina Cruz before the crowds, tourism and media.

When he was young, the points were empty. There were rumors of the odd expat surfer, but Camacho never saw them. He didn’t know the sport of surfing existed, or that those waves he learned to bodysurf would be worth millions in gringo tourism a few decades later.

When he was 18, he took a bus four hours north to Puerto Escondido to work a factory job. There, he would learn that he did not, in fact, invent the sport of bodysurfing.

“They were doing my sport!” Camacho shouted after watching a bodysurfer glide down the face of a wave at the famed beachbreak.

While in Puerto Escondido, he also saw surfers. What a strange sport it was—swimmers, wielding foam and fiberglass, standing erect, swallowed by dark holes in the ocean, reappearing untouched, hands over their heads in rapturous wonder.

Not long after, Camacho was at a flea market. The way he tells the story, he wasn’t looking for anything in particular. He was just strolling around when it appeared. The crowd parted and, in the distance, he saw it. He shoved his way through the masses, approached, haggled and purchased. He brought the old 7’0″ single fin back to Salina Cruz, where he and his friends would stand on the beach at Punta Conejo and trade off riding it. There, he taught himself how to surf.

In the early 2000s, more gringo surfers showed up. In 2006, the Rip Curl Search contest blew up the area to the north, Barra de la Cruz, and word of endless pointbreaks in southern Mexico got out. For a few years, surf media never named Salina Cruz in photos or video, captions just read “Mexico.” But slowly discretion slipped away. Locals advertised surf camps and made rules: If you want to surf here, you have to pay. Gringos who didn’t pay would be threatened. Photographers were charged extra.

“What do you say to people who think the ocean is for everyone?” I ask Camacho.

“We gotta do it, man,” he says. “Look at Puerto Escondido. Locals don’t own land near the beach there anymore.”

Oaxaca is one of the poorest states in Mexico, and gringo surfers with enough disposable income to travel there likely earn more in a month than most locals do in a year. And surf camps don’t keep all the money; instead, surf tourism helps prop up the community. The surf camps pay a kind of “membership fee” to the various subcommunities closest to each wave. The subcommunities then decide where the money will go—a new road, school or medical center.

After the day at Chivo, we drive back for dinner. Camacho’s wife, Linda, makes us fresh fish tacos. She wears a Pink Floyd T-shirt and is just about the nicest person I’ve ever met. On the walls of the dining room are photos of each wave at its best, along with a signed surfboard from World Surf League champion Filipe Toledo, a former guest at Luna Coral.

The window begins to shake.

I put down my fork, wondering if it’s an earthquake. A minute later, it shakes again.

“The swell is here,” Camacho smiles at me. Playa Brasil, the thunderous beachbreak closeout to the north of Punta Conejo is shaking the walls. “Tomorrow, we surf Escondida.”

Escondida is the darling of Salina Cruz. You’ve seen it in surf magazines, summer boardshort ads and Surfline swell features. It’s a hollow sand-bottom vortex, thick as it is tall. The wave is backdropped by a dramatic cliff, gold in the morning light, with cacti clutching its edges. Unlike other points in Salina Cruz, which can range from burgery to rippable, Escondida only has one speed—Ferrari on the Autobahn. Sand builds up along the cliff, and on big swells, the wave revs its engine. On its best days, Escondida has three barrel sections, the last is thickest and closes out into a shallow mortar of sand. If a surfer doesn’t make it out the doggy door, their best hope is to body slam the bottom using the least breakable part of their body.

The next morning, we drive to Escondida. Even before we reach the beach, I can smell the scent of salt and mist from exploding whitewater—swell is in the air. When we arrive, trucks sit on a thin seam of the beach between waves and jungle. I step out of the truck, and like all surfers, try to look stoic and vaguely unimpressed as the best waves I’ve seen in over a year riffle down the point. The inside section is lethal, whitewater’s sailing 15 feet high. Down the beach, a fisherman tries to wash his hands in the shoreline and whitewater rushes up and hits him at the knees, nearly sucking him out. “Hey, peligroso!” shouts one surf guide, as the fisherman scrambles back to shore, soaking wet.

Unlike the rest of us, Camacho doesn’t attempt to hide his excitement. He’s already waxing his board, so I follow. We wait for a lull, sprint paddle out and trade off barrels for the next three days.

Each night, I have no recollection of falling asleep, I simply face-plant, and then it is dawn. I guzzle black coffee, eat bananas, surf to exhaustion and do it again the next day. I buckle my entire quiver, courtesy of the third section at Escondida. My endorphins are shot, my face is sunburnt, my mind is stupid and happy. During the peak of the swell, our photographer, “Chachi,” captures Camacho standing confidently in a barrel. But amid the ecstasy of the swell, I can’t help but feel sad.

Punta Conejo is the southernmost point in Salina Cruz. Chivo is the next point up. Escondida lays just beyond. Sand migration makes each of these points work, and the expansion of the port will very likely turn all three waves into vestiges of the past. As durable as a heaving barrel can feel while crouched inside of it, its power is predicated upon a delicate symphony of billions of grains of sand moving freely across the seafloor and settling in throughout the surf season, unobstructed by cement.

On the final day of the trip, Camacho recommends we check Punta Conejo one last time. The swell has shifted sand and conditions may have improved. We drive down from Luna Coral and up Playa Brasil to the backside of Conejo. The tide is still too high, but the sandbar is better and fun waves run down the point.

“Conejo never disappoints,” says Camacho proudly.

Before we surf, he asks if I want to get a view from the top of the sleeping rabbit. We hike for 10 minutes, digging our feet through sand and ivy. The top of Conejo is a 360-degree view of his surf camp, the wave, mangroves and shipping vessels out at sea. We can even see Chivo and Escondida.

“How did you think to reach out to Save The Waves?” I ask as we stand at the peak of the mountain.

He tells me that he learned about the group years prior, so he emailed them and they responded. Since that email, the director of Save The Waves, as well as board members, have made the trip down. Community meetings are in the works, petitions are online, a plan is being strategized, momentum is on their side. Maybe Camacho is taking on this project for the same reason he ran into the ocean when he was a child, ducking under waves, eventually gliding down the face of one with an outstretched arm; for the same reason he bought a single fin at a flea market and taught himself to surf; for the same reason he paddled out to an expert-only wave on the biggest swell of the season, sliding into shallow, sand-spitting barrels.

No one told him he couldn’t.

By Kyle Thiermann

For more information and details : https://www.patagonia.com/stories/the-wave-below-the-sleeping-rabbit/story-146359.html