Triumph Over Adversity: Wheelchair-Bound Athlete Honored for Climbing Mountain

In 2011, a tragic car accident changed the life of professional Hong Kong rock climber Lai Chi-wai. Once an elite athlete, Lai found himself paralyzed from the hip down. However, this life-altering event did not dampen his spirit or determination. Seven years later, in an inspiring display of resilience, Lai achieved a monumental feat by climbing Lion Rock, a 495-meter (1624 feet) mountain that holds deep symbolic significance for the people of Hong Kong.

A Symbol of Perseverance and Unity

Lion Rock is more than just a mountain; it represents the “Hong Kong spirit” of persistence, resilience, and unity. By conquering this peak, Lai not only realized a personal dream but also sent a powerful message to the world. His climb, which took place on December 9, 2016, marked the fifth anniversary of his accident, transforming a moment of personal tragedy into a triumph of human spirit and capability.

Recognition and Inspiration

Lai’s extraordinary accomplishment did not go unnoticed. He became the first Chinese athlete to be nominated for the Laureus World’s Best Sporting Moment of the month. This prestigious award, founded by Swiss-based luxury goods firm Richemont and German carmaker Daimler, honors the best sportsmen and sportswomen of the year, as well as notable sporting moments. Although Lai did not win the December award, which went to a viral video of a sports stadium in Iowa waving to children in a nearby hospital, his nomination itself was a significant recognition of his achievement and determination.

A Champion’s Legacy

Before his accident, Lai was a four-time champion of the Asian Rock Climbing Championships and the first Chinese winner of the X-Game’s extreme sports. His return to the sport he loves, despite his disability, serves as a beacon of hope and inspiration for athletes and individuals with disabilities around the world. “To me, climbing to the top was accomplishing a dream of mine,” Lai said. “It meant that I could show my friends and supporters that I have overcome one of the lowest points in life: even though I’m in a wheelchair, I can challenge other sports and still be able to do what I love most.”

A Message of Hope

Lai Chi-wai’s story is a testament to the power of perseverance and the human spirit. His journey from the depths of despair to the heights of Lion Rock serves as a powerful reminder that with determination, support, and a positive mindset, individuals can overcome even the most daunting challenges. Lai’s climb is not just a personal victory; it is a universal symbol of hope and resilience, encouraging others to pursue their dreams, no matter the obstacles.

Source : https://au.sports.yahoo.com/

Learn more: https://www.adventurefilm.academy/

Paris Olympics: What you need to know to watch the surfing competition

Paris Olympics surfing competition roadmap:

Athletes take center stage

—Carissa Moore, United States: Olympic gold medalist and five-time world champion has announced she will retire from elite competitive surfing after the Paris Olympics. Three years ago, she won the first women’s shortboard gold medal at the Tokyo Olympics. The 31-year-old Moore, who was born in Hawaii, is widely considered one of the greatest surfers of all time.

—Vahine Fierro, France: The Tahiti-born surfer will compete just 200 kilometers from her native French Polynesia. Fierro gave host France hope of a medal this year after winning the Tahitian Pro Tour called Teahupo’o last month.

—Filipe Toledo, Brazil: The two-time World Surf League champion qualified for this year’s Olympics, but after a poor performance in a competition, Toledo posted on social media that he would withdraw from the remainder of the Championship Tour season. He will step down in 2024. The good news is that Toledo’s manager confirmed to the Associated Press that the 29-year-old Brazilian surfer will compete in the Olympics.

—Jack Robinson, Australia: Robinson, winner of the 2023 World Surf League competition at Teahupo’o, is considered one of the best barrel surfers in the world. That may work in his favor, as the shaft is widely considered one of the heaviest barrels in the world.

Source: https://apnews.com/article/olympics-2024-surfing-tahiti-paris-1f700d46e332532d79882d5e006e215b

Learn more: https://www.adventurefilm.academy/

Jakara Anthony wins Snow Australia Female Athelete of the Year after stunning FIS World Cup moguls campaign

Rarely in the life of a professional athlete is there much time for rest and relaxation — not least in the midst of a record-breaking campaign.

So perhaps it was a surprise to some to see reigning Olympic moguls champion and Harry Potter fan Jakara Anthony wandering through Hogwarts at Universal Studios in Orlando between events.

“It’s fun when we get to do some more touristy things,” Anthony tells ABC Sport.

“The schedule can be pretty hectic, competing back-to-back and week-to-week, but we had a month’s break in the schedule so went to Universal Studios.

“It’s really cool to be able to have some experiences like that.”

Universal Studios proclaims the Harry Potter-themed amusement park “an experience unlike any other,” which is quite fitting.

It also promises a trip to the wizarding bank of Gringotts, which also fits nicely with Anthony’s year.

Because, aside from the obvious parallels of skiing with such grace and skill over the harsh, icy bumps of the world’s toughest moguls fields as if she were flying over them on a broomstick, Anthony has collected enough gold this season to fill an entire vault.

On Thursday night, Anthony capped a stunning season on snow by being crowned Female Athlete of the Year at the Snow Australia awards in Melbourne.

It was an accolade that is richly deserved after the 25-year-old completed a clean sweep of all three World Cup winner’s Crystal Globes on offer, for singles, duals and overall champion.

Anthony’s unprecedented season of dominance saw the Barwon Heads skier win 14 out of 16 World Cup moguls events.

Those 14 victories are the most by any moguls skier in history, three more than the previous mark held by American legend Hannah Kearney.

In fact, Anthony equalled an all time FIS World Cup record for ski and snowboard racers: Swiss alpine skiing superstar Vreni Schneider also recorded 14 victories during the 1989 season, in slalom and giant slalom competitions.

There is a very strong case to be made that she is currently Australia’s most in-form athlete in any sport.

Yet despite the enormity of that success, Anthony remains more focused on the process than the vagaries of the judges.

“I don’t try to take the approach where I’m focusing on the results,” Anthony said.

“Of course, I want to go out there and win every event but I think the majority of the field are out there trying to do that.

“Unfortunately the results are out of my control but for me it’s about going in and focusing on that process, doing all the little bits and pieces that I need to so I can ski the run I’m capable of.

“There were some events where I was having a bit more trouble navigating the course and it wasn’t necessarily my favourite skiing of the season, but I was still able to bring a really good performance there.

“I think I’m getting better at that in skiing the way that I do on more difficult courses rather than just trying to get up and down and survive.

“I had some performances where I was just like, that was one of the best runs I’ve ever completed, so that’s an incredible feeling too.”

On one of the only occasions Anthony didn’t claim gold on the circuit this year, she won a bronze medal in the Dual Moguls event at Idre Fjäll in Sweden in December.

The other time saw Anthony make a rare mistake — “just me misreading the conditions,” according to Anthony — at Deer Valley in February — although she recovered to take out the Dual event the following night.

“That Deer Valley [victory] was pretty special,” Anthony said.

“Every event was pretty cool, they all had different challenges but that duals final against Jaelen [Kauf] was some of the best skiing I’ve ever competed.”

It is not necessarily a surprise that coming back from adversity, however fleeting it was this season, was Anthony’s highlight of the year.

After all, the entire 2024 season was a comeback of sorts after the two-time Olympian took some time away from the slopes at the end of the 2023 campaign.

“I was in a pretty different place when I started this season compared to when last season finished,” Anthony said.

“Winning week-to-week always helps but I was out there having a lot of fun with the team and travelling with a really great crew.

Source: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-05-03/jakara-anthony-snow-australia-athlete-of-the-year/103450642

Learn more: https://www.adventurefilm.academy/

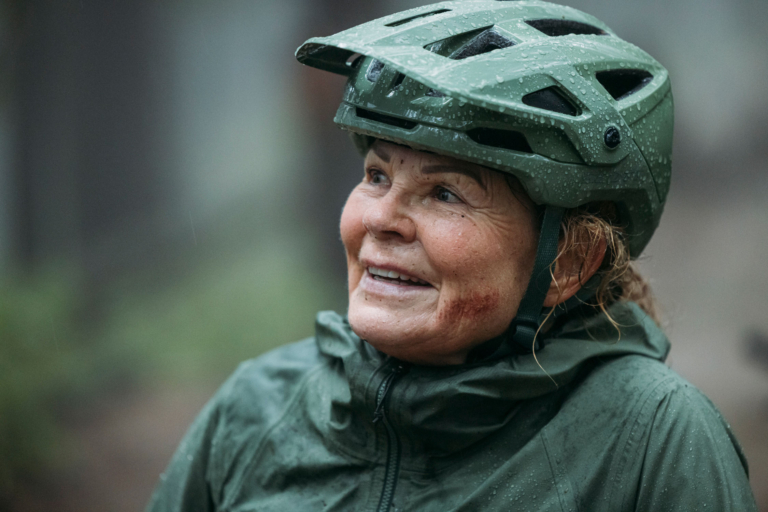

North Shore Betty

After nearly 30 years on the hallowed trails of southern British Columbia, Betty Birrell still thinks life is one big playground—and that you’re never too old to send.

It’s a typical fall day in the forests above North Vancouver, British Columbia. The rain is coming down so hard you can’t see more than a few hundred feet, almost obscuring the cedar trees swaying in the surrounding murk. Wind whips between the column-like trunks, making waves through a sea of emerald sword fern. A crack! slices through the rain as a small tree snaps and falls into a nearby stand of Douglas fir.

If Betty Birrell and her son, Hayden Robbins, are fazed by the weather, they don’t show it. Their bikes seem to float down a river of contorted roots, greasy rocks and slippery wooden bridges as if it’s a mild day in June, with Betty leading through the vilest conditions. It’s amazing to watch. She is much, much more confident on these trails than I will ever be, and I’m half her age—and a former professional mountain biker, though I feel embarrassed to admit it at the moment.

At 73 years old, Betty has called these trails home for almost 30 years. In the early 1990s during her mid-40s, she bought her first mountain bike, and a good friend she refers to only as Old Rob took her down 7th Secret, a trail on Mount Fromme. Her second ride was on the aptly named Executioner, another steep, rooty, technical fall-line descent. Both trails have retained their black-diamond rating, and even on the plush full-suspension bikes of today, most riders would find Executioner terrifying.

Her face lights up at those memories. “I was hooked right away.”

Betty’s entrance into mountain biking—as a single mother a few years short of 50, raising a 6-year-old while flying overseas each weekend as an international flight attendant—is unconventional, by most measures. But to start on Vancouver’s North Shore during the 1990s … well, that’s another level of gnarly. Clinging to the mist-shrouded slopes of Mount Fromme, Mount Seymour and Cypress Mountain above North Vancouver, “The Shore” is to mountain biking what Yosemite is to rock climbing or what O‘ahu is to surfing: Few other places have done more to influence and define the sport. And, like the Dawn Wall or Pipeline, it is not for the faint of heart.

“Some people say that California invented mountain biking,” says local trail builder Todd Fiander. “The North Shore invented mountain biking.”

The Shore’s infamous trails are a cross between a BMX track and an Ewok village, a convoluted web of wooden ladder bridges, rock drops, berms and “skinnies”—narrow, raised features intended to be ridden across. Some of this woodwork climbs into the trees, demanding riders navigate catwalk-like planks, sometimes only 6 inches wide and as high as 20 feet above the forest floor. Other features roll multiple stories down near-vertical rock faces.

Right: Built by “Dangerous Dan” Cowan, the Flying Circus trail on Mount Fromme represents the absurd pinnacle of the North Shore’s renegade early years. It had the skinniest, highest and most dangerous features anyone had ever seen and could only be ridden by a handful of people. Trails like Flying Circus were decommissioned as mountain biking became more widely adopted, but the remnants speak to the enduring legacy of cedar planks, mad creativity and an unrelentingly desire to push the limits. Photo: Jordan Manley

“Shore-style” trails can now be found across the globe, but when Betty started riding in the early 1990s, locals had only been building them for a few years. Todd—or Digger as he’s known in the mountain bike world—is considered the first to incorporate ladder bridges and raised wooden structures into his trails. He’s observed nearly every notable rider on The Shore for the past three decades and captured many in his 11 North Shore Extreme films, including—to my surprise and, I must admit, chagrin—Betty.

A few years ago, I made a documentary about the history of free-ride mountain biking, much of which happened on Digger’s trails, yet I hadn’t heard of Betty until this past year. I’d seen her, however, while poring through hours of Digger’s grainy camcorder footage. I just didn’t know it was Betty.

“She was the first person to ride The Monster,” Digger says, referring to an iconic stunt commonly regarded as the first “roller coaster.” (It looks exactly as it sounds, just made with slats of split cedar.) “I had just put the last plank down and asked her to ride it for me, so I pulled out my camera and filmed her. The third time, she fell and pulled out her shoulder, and I had to pop it back in. And I think she was like 55 when she did that.”

Betty recounts those early days so casually, it takes me a few minutes to realize how insane her entry into the sport was. In the early ’90s, body armor was rare and full suspension and hydraulic disc brakes were nonexistent, making the bikes as much of a liability as a lack of skill.

“Fortunately, I didn’t really have a fear of falling,” she says. “Still, I was covered with bruises, black and blue. I couldn’t go out wearing shorts because it looked like someone took to me with a baseball bat.”

But full-send is how Betty operates, under the radar or not. Born in the rural town of Chemainus on Vancouver Island, Betty moved to the city of Vancouver to study geography at the University of British Columbia, where she joined a crew of fellow climbers who got after some of the biggest peaks around Vancouver.

“In the ’70s, she was part of this really hard-core group of climbers that had all sorts of first ascents in the area,” says Hayden, who is a professional ski guide and operations manager for Whitecap Alpine Adventures. “But they wouldn’t claim them because they didn’t want people to find the zones.”

Betty picked up windsurfing a few years later and by the early 1980s had become one of the top female windsurfers in the sport, flying out of huge 30-foot waves the likes of which no woman had done before. As an editor for Sail Boarder Magazine put it in 1982, “Betty Birrell is a superstar of the sport … a leader of the leading edge … ranked on par with most top men.” The German magazine Surf summed it up even more succinctly in a headline from their June 1982 issue, “Betty Birrell: The Best Female Surfer in the World.”

She stationed herself in Hawai‘i, working as an international flight attendant while surfing big waves between shifts. She married a fellow Canadian three years into her time on the island but continued to commute between Hawai‘i and British Columbia for a year so she could sail. Eventually, Betty returned to Canada and, at 39 years old, gave birth to Hayden.

“I think motherhood is the best adventure ever, really,” she says. “I was so surprised how much I loved being a mom, how much I loved being pregnant.”

Just before Hayden’s second birthday, her husband left them. She recalls an argument before the split, “He said, ‘You just think life is just one big fucking playground!’ And I said, ‘Well, yeah!’ I thought it was a compliment.”

As a newly single mom, Betty worked overseas flights on weekends while Hayden stayed with his dad or grandmother, and she’d return for Hayden’s bedtime on Sundays. “You just kind of adapt as you go along,” she says. “I just reinvented adventure. Instead of going mountaineering or stuff like that, we’d go car camping with my parents, and it was just so fantastic.”

Betty’s face glows when we talk about anything mom-related. She asks to see photos of my kids and swoons at the sight of them. Above the stairway in her home is a huge photo of her and Hayden beaming after a day of cat skiing together.

“Mountain biking was the perfect activity for a single mom because it was right outside our door and easy for [me and] Hayden to do together,” she says. “I would pick him up after school, and we’d dash over to Fromme for a ride.”

Hayden remembers her enthusiastic coaching and patience on the trail. At an age when most kids want their parents to park around the corner to avoid being seen by their friends, Hayden welcomed his mom joining him and his friends on rides. “It’s amazing when you get on a technical trail with her,” he says. “She just zips along like you wouldn’t believe. She’d be better than my buddies, so that was a funny dynamic.”

Let me just say that if my mom were mountain biking alone down double-black diamonds, I would probably give her a tracking device or an emergency beacon. But Betty isn’t my mom. And I’m not Hayden. “My concern for my mom is overridden by knowing she is so experienced,” he says. “She is the consummate mountain woman.”

Some people, however, notice her age before her ability. Occasionally, she notes, when coming upon fellow riders assessing stunts on the trail, “They see I’m older, and I’m a woman, so they just stay in the way because they think I’m not going to be able to ride it. I just say, ‘Excuse me, I think I’m going to ride on through.’ I actually like that because I feel like I’m doing a service for women—older people, too, but especially for women.”

But with all sports, injuries happen. Like that time she broke her leg hard-boot snowboarding. Or when she broke both her hands riding the infamous Rippin’ Rutabaga rock drop in the Whistler Mountain Bike Park in 2003.

“I remember lying on the ground,” she says. “I was 54 then, and I knew I was hurt badly, but I didn’t want to tell the bike patroller how old I was.”

Hayden was 15 at the time and returned home to find his mother immobile from the shoulders down. “She had these crazy wrapped arms, lobster-claw things,” he says, “and she couldn’t do anything.”

At age 58, Betty took early retirement and started her own landscaping business; she still helps friends and family with their yards occasionally, though no longer as a profession. These days, she mostly rides alone: Most of her bike buddies work during the week, and Betty avoids riding on weekends (the trails are too busy, she says).

And, of course, she still rides with Hayden whenever he’s home. Hayden now lives in Revelstoke, British Columbia, and whenever he talks about his mom, he’s visibly proud. “For me, she’s laid the path that I’ve followed in my life, and it’s a different path than a lot of people,” he says. “But she’s always been the biggest supporter and inspiration.”

Almost 30 years after her first lap down Executioner, Betty admits she’s scaled back her riding (she avoids skinnies in particular), aware that a bad crash could have larger consequences than when she was younger. But she still sends. Not because she’s fearless. She just knows better.

“It is calculated,” she says. “You know your limits. Sometimes you push a little bit too much and you get away with it. But you know your limits, and you know what you want to do.”

Back in the fall storm, we call it a day and say our goodbyes. As I pull out into the pouring rain, I’m left with an overwhelming sense of permission to try all those things I’d convinced myself I was too old for. I’m not aging out of the fun and games of my early 30s; after a day with Betty, I feel like the good times are just beginning.

“When I was 50 years old, I never thought I’d be able to ride a mountain bike fast down a trail at 73,” she says. “It’s interesting how your perception of age changes as you get older. I would love to be 65 again. Isn’t that crazy? Who would have ever thought. The biggest thing I’ve learned is to appreciate where you are.”

By Darcy Hennessey Turenne

For more information and details : https://www.patagonia.com/stories/north-shore-betty/story-119987.html

Living on Easy

A trip to Amami Ōshima, Japan, transports Gerry Lopez to a familiar feeling on a distant land.

I was born in Honolulu in the late 1940s, before Hawai‘i was a state. In those early days, the living was easy. It was called “island style,” and that was the way everyone lived … well, at least everyone we knew. The beach across from the zoo was where we spent afternoons after school and on weekends. There were tourists down near the hotels and at the Sunday lū‘au at Queen’s Surf, but otherwise, the rest of Waikīkī Beach and Kapi‘olani Park was mostly locals only. My mom took my brother and me surfing one day at Baby Queen’s, and none of us, Mom included, had any idea that life going forward would inexorably shift to another path. We’d both been bitten by the surf bug that day, but it was Victor who felt it first.

His school buddy, Stanford Chong, and his whole family surfed together, so before long, Vic had his own surfboard and was surfing with them all the time. They owned a country house on the beach on O‘ahu’s East Side between Crouching Lion and Chinaman’s Hat (Mokoli‘i), and often I’d be invited to spend the weekend there since Stanford’s sister, Marlene, and I were classmates.

They had a large house with a big yard and some sprawling hau trees around an outdoor barbecue and firepit. We would drive out from Honolulu town, over the Pali, through Kāne‘ohe town, along the windward side—the ocean on our right and majestic Ko‘olau Range on the left. The East Side gets rain almost daily, so everything is green and growing. In the morning, we’d walk the beach to find any Japanese glass floats that may have washed ashore, although the grown-ups always got the jump, waking earlier and knowing where to look. After breakfast, sometimes Mr. Chong would take the boat out with all the kids and fish a little or explore Chinaman’s Hat or spearfish the reefs in front of the house.

Somewhere along the line, and without even understanding it was happening, I developed a little boy’s affinity for this side of the island. It was like falling under a spell … there was its special feel, look, smell and idiosyncrasies. Like when the trade winds blew, I learned to be on the lookout for Portuguese man-of-war and so avoid its painful sting. Or noticing how vivid and bright the stars were on dark nights, without the town lights to spoil them.

I had no idea at the time, but later on, when older and looking back, I realized how idyllic that was—life at that young age is full of questions, uncertainty and finding oneself on shaky ground. But those times on the East Side were like putting aloe vera on a burn; there was a very distinct, soothing ahhh about it, and I looked forward to each time we got to go.

In a way, life is a little like Dad’s car … it takes us down the road, and at some point, a stop at the service station is needed to keep going. The weekends at the Chongs’ beach house were that gas-station stop. Then things changed. I began to run on another kind of fuel; surfing started to rear its head and fill my tank. I don’t think I even realized that one had replaced the other, or if replace was even what it did. Surfing, as the complete endeavor, inevitably takes not just some of one’s time—it takes it all. A deep passion develops, and while it’s all one wants to do, at the same time, it stokes a great fire down inside that drives a person to … well, to be insatiable for even more of it.

Perhaps that earliest harmony at the Chongs’ had something to do with it, but I found myself living in Kahalu‘u, way out on the East Side, and spending a lot of time in the car driving: either to town for my surf-shop business, Ala Moana for summertime surf or the long haul to the Country in the winter for the waves there. Sometimes if I was a passenger, I would look at the Chong house as we zoomed by. I never saw anyone; a couple of times I stopped, but it was empty and the sweet and tangy awareness that I used to have was no more. But surfing was keeping my gas tank full, so I guess I didn’t miss it.

Life happened and the years flew by. In 2017, the film crew at Patagonia suggested a documentary film project that must have been meant to be because it unfolded like a spinnaker sail does when a stiff wind blows—not that it was without a few wrinkles—but by spring last year we were ready to premiere it.

A tour ensued throughout the US, Europe, Australia and Japan. The director, Stacy Peralta, did most of the stops with me except for Japan. He was busy, so I went alone. In the undertaking of this assignment, we never thought that something like COVID-19 would have such an effect, but it surprised the entire world and certainly put up some hurdles for our movie tour. Japan had only just opened its doors to visitors when I got there. We had showings in Kamakura, Sendai, Tokyo, Osaka and Fukuoka: all cities where I had been before, with old friends in all of them, and the film showings went like clockwork.

The final stop was Amami Ōshima, one of the little islands near Okinawa that I’d heard about but never visited. The monkey wrench was that a typhoon with an unpredictable trajectory was aimed toward the same place we were bound for. For most people, a typhoon warning is usually a good reason to reschedule one’s trip. For a surfer, however, this is a sure sign of surf coming and serves as an attraction rather than a deterrent, and our entire Patagonia Japanese crew were surfers. Of course, we went.

As we flew into the airport, the ocean looked spectacular from above, deep blue with strong trade winds blowing whitecaps and swells toward the islands. Staring out the window, I was mind-surfing those waves on a downwind SUP or a wing foil.

We landed still in our city clothes, long pants, shoes. But all our friends in the terminal were waiting for us in shorts and slippers. Yeah, man, at a glance, I could tell they were all living on easy. I couldn’t wait to change clothes and join them. As soon as I walked out the plane’s door, something happened … a feeling, a smell, the green hills. I don’t know what it was, but I felt like I was back to some place I had been before. I looked more closely. The plants and trees were familiar, the ocean had a windswept look I recognized and waves were breaking in crystal-clear water over coral reefs, sandy beaches; it felt like I should know it even though I didn’t.

We were greeted with leis by some old friends and many new ones who had an easy, friendly, familial excitement. Driving in the car back to our host’s home and surf shop was eerily déjà vu, too. When we stopped, I quickly changed into my shorts and slippers and just that made me feel more at home in these surroundings.

A quick walk down to the beach to connect with the sand and the water, touching them and seeing the weathered siding on the homes that comes from living on a windward shore, gave me an astonishing revelation for the strong sensations I was having. I was back at the Chongs’ house on the East Side from 65 years ago—that loving feeling had never left. It just needed the right coaxing to come rushing back like it always had before. Good feelings are strange and powerful. We usually take them for granted as we revel in them, never thinking how deep they go or how long they’ll last. The rest of our trip was totally smooth and seamless, as one would expect with family and friends. We drove to the other side of the island. For me, the whole way looked and felt like Hawai‘i. We surfed excellent waves with dear friends, ate great food, talked story—life was very good.

The next day we showed the film to the local surf community. They were an awesome audience. That evening, with the hurricane hovering just over the horizon, we flew out, arriving late into Tokyo. The typhoon hit Okinawa, but maybe all the good vibes were strong enough to cause the storm to veer away from Amami Ōshima.

It was a wonderful trip, “island style” the entire way and one I won’t soon forget. I left the little island and its tight surf community with an absolutely full tank of premium-grade fuel. I’ll just bet that everyone else was topped off, too.

By Gerry Lopez

For more information and details : https://www.patagonia.com/stories/living-on-easy/story-141483.html

WHAT is the adventure film festival:-

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their bliss.

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their work.

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their videos.

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their expertise.

The Adventure Film Festival is a global online adventure film competition.

IF you have an adventure film worthy of global recognition = submit it.

IF you are an adventure film maker = build your story / build your brand; it is our job to help you build your business.

Adventure Film makers / our stars – we want to help you develop our global industry…

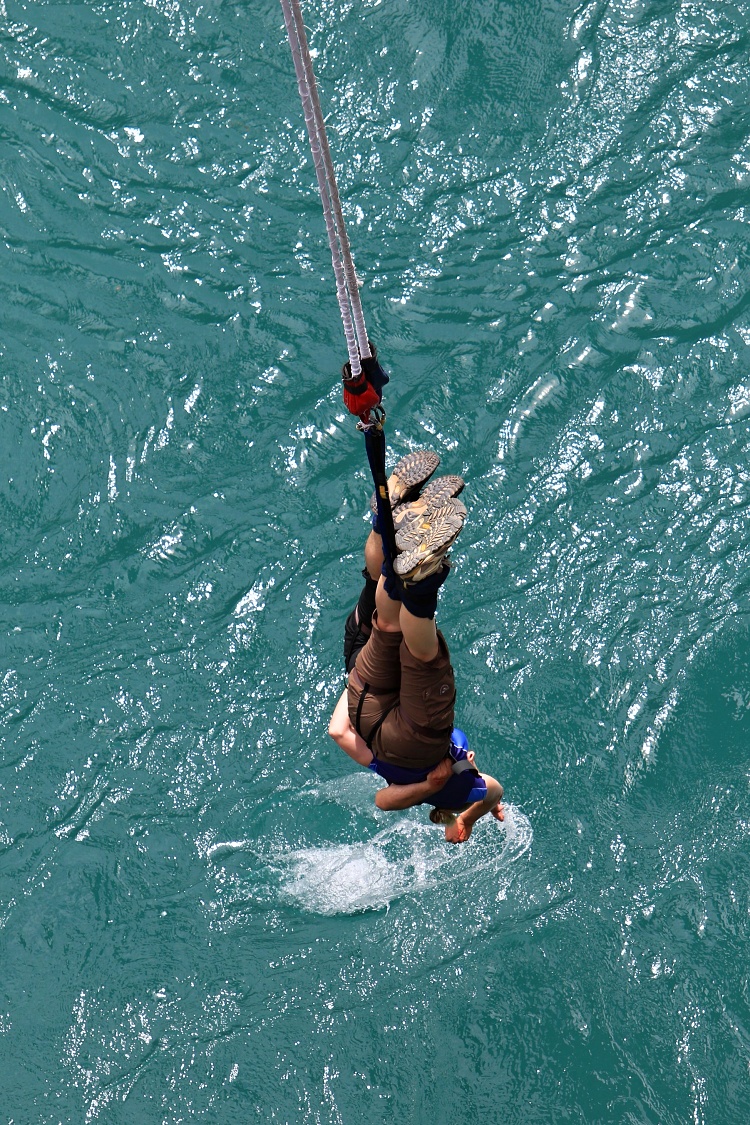

FIRST-TIME BUNGEE JUMPING – WHAT IT’S REALLY LIKE (KAT’S STORY)

We love adventures.

We have done rock climbing, zip-lining, diving, swimming in a cage with sharks, white water rafting, skydiving and extreme roller coasters.

You name it, and either we have done it, or it is on our bucket list.

Bungee jumping had been on our list for a long time.

But in the end, it proved much harder than it seemed in photos and videos.

Bungee jumping took our adventures to another level, and we learnt a few life lessons.

While we were on our last road trip in New Zealand, we knew this was the best place to try it.

New Zealand is the birthplace of bungee jumping, which has been popularised here.

The country is also renowned for innovation, excellent facilities, many years of experience and, most importantly, an excellent safety record.

Queenstown is called the ‘Adventure Capital of the World’, so we felt that we should do our first jump there.

This post has been written from Kat’s point of view because this has been a rather personal and intense experience.

Petr’s self-preservation instinct is quite relaxed compared with most people, so his experience made for another story. You can read it here.

BUNGY OR BUNGEE?

Both words have the same meaning.

Bungy is the spelling used mainly in New Zealand, while bungee is more common in the rest of the world.

SKYJUMP LAS VEGAS

The list of adventures I have been through is long, and I’m proud of that.

There is only one exception, SkyJump Las Vegas, the world’s highest controlled descent.

The launching pad is located on the 108th floor of the Strat Hotel, Casino and SkyPod (formerly Stratosphere Casino, Hotel & Tower), 260 metres (855 feet) above the Las Vegas Strip.

While in Las Vegas, we decided to do the night jump. What could go wrong, right?

I was confident because we had just done our first skydiving in Cuba a few months before, and I loved it.

We had jumped out of an old aeroplane 3 km (1.9 miles) above the ground, so it couldn’t be worse, right?

I was wrong. It was.

I was fine until I got to the jumping platform, where everything changed.

When I started to feel the wind on my face, I realised what height I was at.

I was supposed to jump into the dark but could not do it. My confidence was gone.

I chickened out.

What was so different between skydiving and this jump?

I was on my own. There was no experienced instructor I could hang on to.

I took the challenge too lightly.

On the other hand, Petr managed to jump. The fee we had paid was non-refundable, so he jumped twice not to waste the cost of my ticket. How cool is that?!

KAWARAU BRIDGE BUNGY, QUEENSTOWN

When we arrived at Queenstown in New Zealand, I knew that if I didn’t do it here, I would probably never do it.

But after I failed in Las Vegas, I was afraid I would give up again.

At first, we visited the Kawarau Bridge Bungy to see what it was like.

It’s the world’s first commercial bungee, with a height of 43 metres (141 feet).

The location was beautiful – a wooden bridge in the Kawarau gorge overlooking the river with its turquoise water.

But the scenery was the last thing on my mind!

People were queuing for the jump. There were many of them – men, women, young, middle-aged…

They all seemed to be just ‘normal’ people, no adrenaline junkies.

I thought that I could do it too if they could do it.

I had done so many potentially dangerous activities before and didn’t want to look like a coward now.

The faces of people who were just about to jump said it all.

They were afraid, really afraid.

I realised that everyone felt fear (except for those adrenaline junkies).

And that’s what it was all about – overcoming the fear and doing it despite it.

So, we decided to jump the following day.

Unfortunately, we mentioned this to the Airbnb host we stayed with that night.

Instead of a few words of encouragement that we needed, she said that bungee jumping was the worst experience of her life.

After standing on the jumping platform for ages, she only jumped (with closed eyes) because her friend threatened to push her.

It didn’t help at all. It wasn’t something I needed to hear.

As you can imagine, I didn’t get much sleep that night.

I went from “Yes, I can do it, I have done worse things.” to “What is the point of doing it if I won’t enjoy it? Let’s leave it till another time. ”

In the morning, I still didn’t know if I was going to do it or not.

We arrived at the Kawarau Bridge and watched people jumping for a while.

Petr asked if I was in so that he could buy the tickets.

I still didn’t know what to do. I hated to admit that I was so scared.

We agreed that Petr would jump first, and then I would decide if I wanted to do it or not then. He managed a beautiful dive; it looked so easy. He told me it wasn’t too bad and I should do it too.

I still didn’t know what to do.

Then, we saw a couple preparing for a tandem jump (the girl was so scared that she didn’t do it in the end).

I thought it would be easier to jump together with Petr because I could hold him.

If anything went wrong, he would know what to do (he always does!).

I knew if I didn’t do it here and now, I would never do it because I would find another excuse.

A tandem jump was available, and we bought the tickets.

We got weighted, signed a waiver and put on our harnesses.

We were told which way to jump and hold each other for a smooth experience.

The preparations took longer because they had to calculate the correct length of the ropes for two people jumping together, which wasn’t that common.

Each of us was tied to a separate rope, and we held each other behind our backs.

Petr got ready first because he was taller.

Then, it was my turn.

The staff were excellent; they made fun and talked to us all the time to make us feel more relaxed.

I had a smile on my face, but when I got to the jumping platform, I felt paralysed by fear.

I could barely move.

But I didn’t question the safety of the ropes.

It was the feeling of having to jump into space from such a height.

I was trying not to look down and was looking at the surroundings.

I was forcing myself to think about something else, but it was hard.

And there we were – standing on the jumping platform, tied to each other, smiling for the cameras but freaking out inside (at least I was!).

It felt like being in a movie – and then the guy said: “You are ready to go – three, two, one, JUMP!”

And we jumped.

I let go and DID IT.

I managed to jump at the exact second as Petr.

It was a special moment that we shared.

It was just a split second until gravity grabbed us, and we started falling.

Then I didn’t remember anything until we reached the water.

I don’t know if I passed out or if it just happened so quickly that my brain couldn’t process it.

But I was probably fully conscious because Petr told me later that I was screaming the ‘F’ word all the way down!

We were thrown up and down like two puppets when we got down to the river, and the ropes stretched.

The fear was gone, and we were laughing and enjoying the moment.

After we stopped moving, a boat came underneath us and picked us up.

I was shaking but so happy that I had made it.

But deep inside, I knew I needed to do it alone.

I was a step closer to that now.

Petr hadn’t had enough and wanted to conquer the nearby Nevis Bungy too, because we were leaving Queenstown the following day.

It’s New Zealand’s highest bungee (134 metres, 440 feet). People jump from a cable car cabin hanging between two mountains.

I wasn’t ready to do that because I was still processing our tandem jump. Just standing in the unsteady cabin was scary.

Fair play to Petr that he managed to jump as effortlessly as only he can.

AUCKLAND BRIDGE BUNGY

Two weeks later, we arrived in Auckland.

I knew it was my last chance to jump on my own because we were leaving New Zealand soon.

The Auckland Bridge Bungy was perfect because the jump was above the sea, so I convinced myself that nothing could happen.

If anything went wrong, I would end up in the water, right?

We booked our tickets online and got picked up by the minibus.

We put all the gear on, got a quick safety briefing and off we went.

We had to walk to the middle of the Auckland Bridge to get to the jump pod.

At the moment, the bridge is not accessible to pedestrians.

The only way to get stunning views of Auckland’s skyline is the Bridge Bungy or Walk.

The walk to the pod felt never-ending.

I was trying to distract myself by looking around and thinking about anything else but the jump.

Petr was the most experienced jumper in the group, so he went first.

He decided to jump backwards – how crazy is that?!

He requested the ropes to be adjusted to get as deep into the water as possible.

He dived up to his knees.

When he came back up, he was laughing as if it was all just a piece of cake.

Two more people were jumping after him.

I could see that they were scared, but they made it.

Then, it was my turn.

Again, the staff were terrific.

They were making jokes, but nothing could help me at that stage.

I was trying to keep calm, but I was so frightened that I could barely move.

I felt like a robot, just doing whatever I was told.

But I had decided to do it no matter what, so I kept going.

The guys got my rope and gear set so I could touch the water as I requested.

They helped me to get to the jumping platform.

That was it.

Now or never.

I was standing on the platform, trying not to think about what I would do and admiring the bridge’s impressive construction to distract my mind.

I was freaking out.

A few smiles for the camera, and then they said: “Three, two, one, JUMP!”

And I JUMPED!

I just leaned forward, and gravity did the work for me.

The horror of the last few seconds before the jump suddenly changed into pure joy when I started falling.

I was enjoying the moment and smiling until I hit the water.

It didn’t hurt at all, and I got into it smoothly.

I dived up to my waist, which I didn’t expect.

I had my mouth open and tasted the salty water.

In the end, this was the best part of the experience.

I couldn’t believe that it was over and I MADE IT! I came back up shaking but happy.

This time I enjoyed the views on the way back to the mainland.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Bunge jumping was the hardest thing I have ever done (so far).

I had never felt so much fear before.

But at that moment, when I was jumping on my own, I realised one crucial thing that has profoundly affected my life.

I realised that I could really do ANYTHING I wanted.

It might be scary, hard or seem impossible.

But if I really want it, I can find the way by taking small steps forward.

And if I can do it, you can do it too (whatever it is).

PS: When we return to Las Vegas one day, I will jump off the Stratosphere Tower…. I know I can do it now…

For more information and details : https://travelfromsquareone.com/first-time-bungee-jumping/

adventure surfing movies

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their bliss.

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their work.

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their videos.

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their expertise.

The Adventure Film Festival is a global online adventure film competition.

IF you have an adventure film worthy of global recognition = submit it.

IF you are an adventure film maker = build your story / build your brand; it is our job to help you build your business.

Adventure Film makers / our stars – we want to help you develop our global industry…

WE hope you enjoy the news / videos / ALL that we do for you…

This is your 1-stop home cinema for the best surf movies playing online

Summary

-

1The Source

-

2For The Dream

-

3The Seawolf

-

4Skimboard Nazaré

-

5à la folie

-

6Beyond the Lines

-

7Shaping Jordy

-

8Shaka

-

9OUTDEH

-

10The Other Side Of Fear

-

11Riss

-

12And Two If By The Sea

-

13Coldwater Journal

-

14Fish

-

15Under An Arctic Sky

-

16South To Sian

-

17Generations: The Movie

-

18Paradigm Lost

-

19Chasing the Shot

-

20Let’s Be Frank

-

21Strange Rumblings in Shangri La

-

22One Shot

-

23Exploring Madagascar

The Source

33 min

The Source

Koa Smith goes on a South African surf adventure, where waves (or lack thereof) lead to profound discoveries.

For The Dream

1 h 35 min

For the Dream

Ex-pro surfer Ben Gravy sets out on his dream to become the first person to surf in all 50 US states.

The Seawolf

43 min

The Seawolf

Award-winning filmmaker Ben Gulliver follows seven surfers on a two-year journey in remote, freezing waters.

Skimboard Nazaré

28 min

Skimboard Nazaré

Brazilian skimboard world champion Lucas Fink faces Portugal’s iconic Nazaré wave with a skimboard shape.

à la folie

33 min

à la folie

Strap in for the ride of your life as we follow Justine Dupont through a ground-breaking big wave season.

Beyond the Lines

43 min

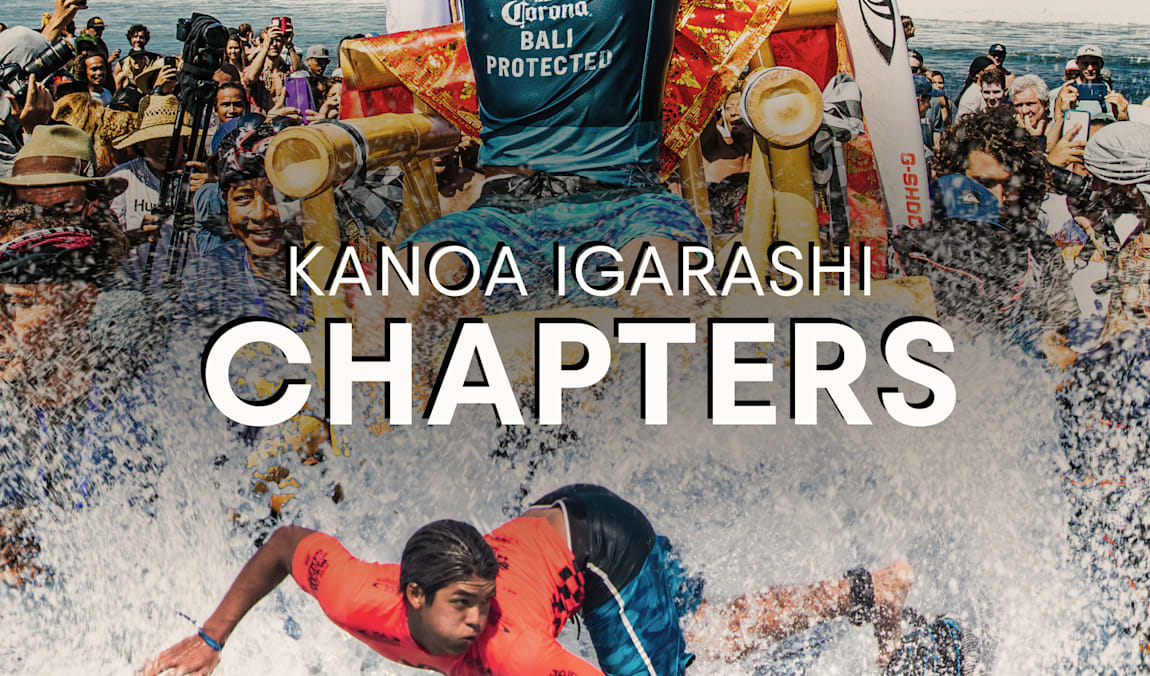

Chapters

Travel with surf star Kanoa Igarashi for insider access to the World Championship Tour.

Shaping Jordy

48 min

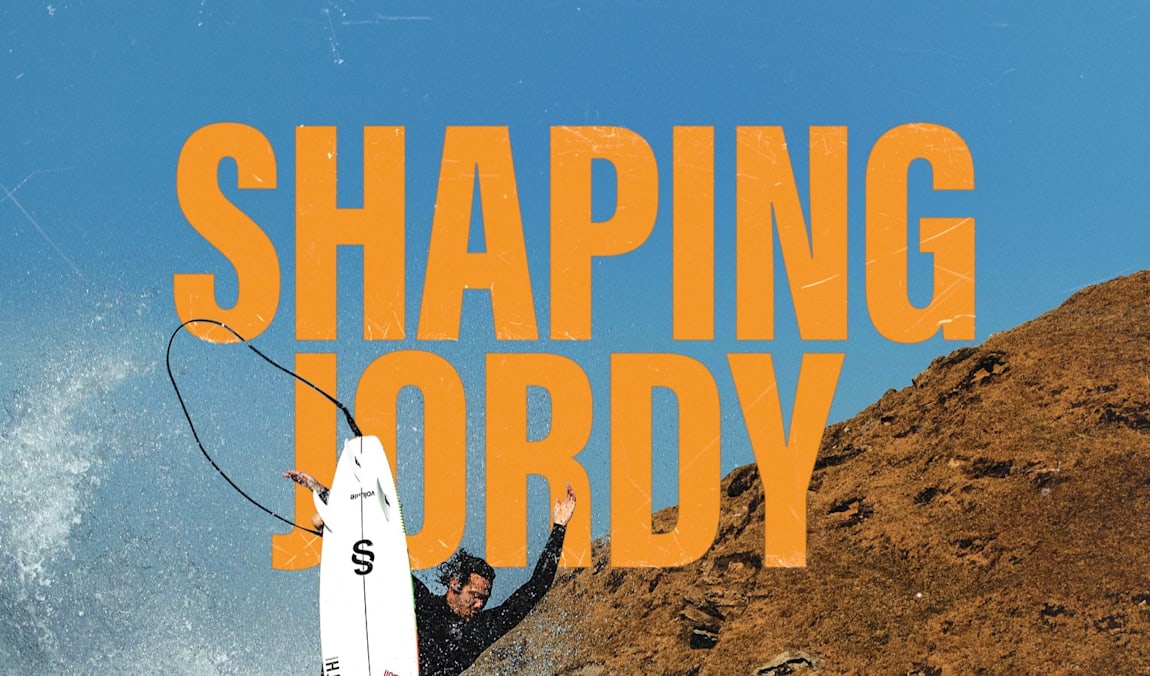

Shaping Jordy

Ride along with Jordy Smith and Mikey February as they cruise the South African coast in search of waves.

Shaka

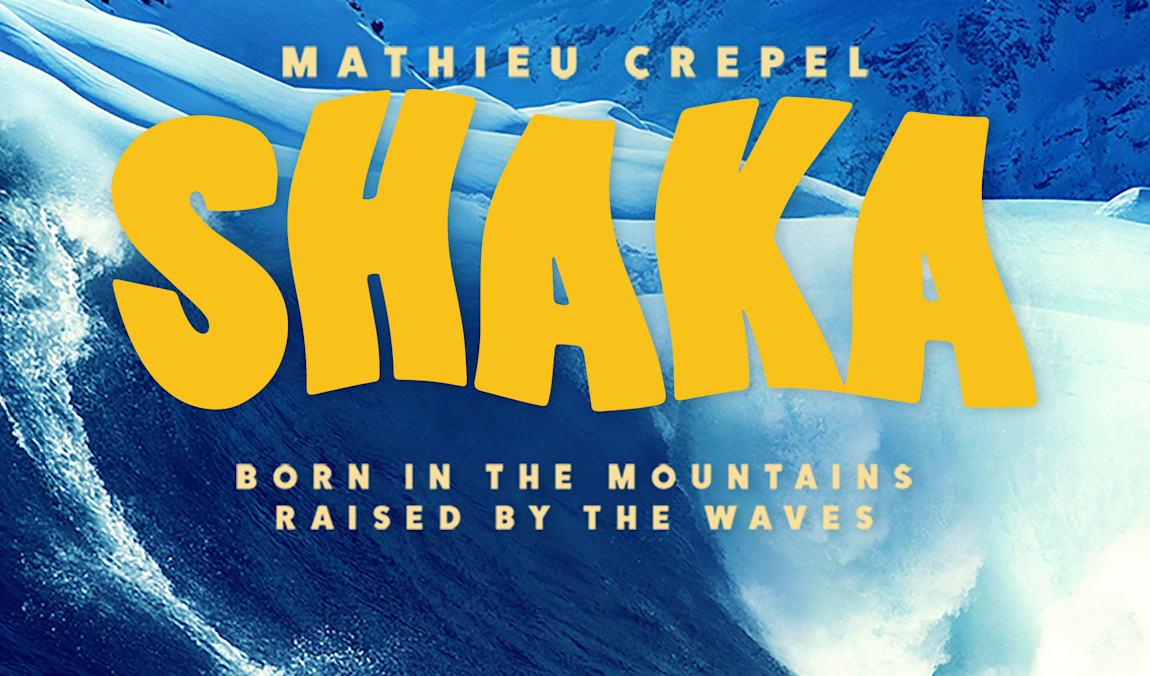

1 h 17 min

Shaka

Mathieu Crépel shifts his focus to the ocean and takes on one of the world’s biggest waves – Jaws.

OUTDEH

1 h 18 min

OUTDEH

Three young Jamaican men share their stories: a rapper, a surfer and a resident of Tivoli Gardens.

The Other Side Of Fear

58 min

The Other Side of Fear

The inspirational tale of big wave surfer and keynote speaker Mark Mathews and his journey back from disaster.

Riss

41 min

RISS

From director Peter Hamblin, follow surfer Carissa Moore around the 2019 World Surf League Championship Tour.

And Two If By The Sea

1 h 43 min

And Two If By Sea

Watch the iconic story of sibling rivalry between pro surfers and identical twins CJ and Damien Hobgood.

Coldwater Journal

43 min

Coldwater Journal

Follow surfer and filmmaker Ben Weiland on his decade-long journey to explore the world’s coastlines.

Fish

1 h 22 min

Fish

Discover the origins of fish surfboards and meet some of the pioneers who changed surfing culture forever.

Under An Arctic Sky

40 min

Under an Arctic Sky

A group of surfers, along with photographer Chris Burkard, journey to Iceland in search of perfect waves.

South To Sian

2 min

South to Sian

What began as a three-month surf trip off the beaten track turned into a two-year odyssey of exploration.

Generations: The Movie

38 min

Generations: The Movie

Join generations of pro surfers as they give an ode to the old days while looking to the future.

Paradigm Lost

1 h

Paradigm Lost

Featuring Waterman Kai Lenny

Chasing the Shot

23 min

Chasing The Shot – Leroy Bellet

Come join Leroy Bellet on the hunt for the photo of a lifetime, from his home waters on Australia’s South Coast to the notorious Teahupo’o in Tahiti

Let’s Be Frank

50 min

Let’s Be Frank

Who is Frank Solomon? A man? A myth? The two might just be inseparable.

Strange Rumblings in Shangri La

52 min

Strange Rumblings in Shangri La

A Worldwide Surf Expedition

One Shot

Exploring Madagascar

26 min

Exploring Madagascar

Slade Prestwich, Frank Solomon and Grant ‘Twiggy’ Baker embark on an epic surf adventure to Madagascar.

Trails for Everybody

An interview with Gabo Benoit, trail advocate and mountain-bike mayor of Coyhaique, Chile.

Despite the pandemic, Gabo Benoit hasn’t stopped advocating for trails around his home in Coyhaique, Chile. Writer Teal Stetson-Lee caught up with Gabo via Zoom, to hear more about his recreation-based conservation efforts and the evolution of mountain biking in the Aysén region.

I first met Gabo in February of 2019 at his home in Coyhaique, where he was cheering on his daughters, 7-year-old Amalia and 5-year-old Maite, as they fearlessly rode their bikes off tiny wooden jumps in the backyard. It was a fitting intro, and the whole family immediately welcomed us.

As it turns out, Gabo also has a history in professional mountain biking as a national champion downhill racer and Enduro World Series competitor. His racing experiences reflected his unconventional approach to life and served as a catalyst into his current roles as a mountain-bike guide and Patagonia brand ambassador in Latin America. Gabo’s dreams and goals have always been bigger than bike racing, having dedicated himself to strengthening his community and homeland against economic hardship and environmental destruction.

Gabo and I share a deep interest in the convergence of outdoor recreation, conservation and community, and we’re glad you’re all joining us as we continue that conversation. Welcome.

Teal Stetson-Lee: Hello, Gabo! It’s great to see you. Where are you right now? And what are you up to?

Gabo Benoit: Well, well. Hello, Teal. Nice to see you too. I’m here in the store. The store is now closed for two hours. I’m in Coyhaique. It’s a beautiful day outside. I’m great.

TSL: Wonderful! So, give me a little bit of background on yourself in a few sentences.

GB: A little bit background, like little words for me? Adventure! I don’t know what else. My life is an adventure. My whole life has been like that, taking things in one minute and trying to make it out and always focusing on what I love in my life: wheels, nature and conservation. I think they’re so important, those things for me.

I started coming down here to Coyhaique and Patagonia [the region] when I was really little. I was like 8 years old, and I was involved in fly fishing. An uncle of mine told me how to fly fish, and that was a real connection with nature and everything. I think my uncle was not so happy because this little kid was here every summer, trying to go fishing.

From 4 years old, I was involved with two wheels. I started racing dirt bikes, motocross. My father is a fanatic about rally cars and everything with wheels. Bikes and mountain bikes were in me since I was 4, but the connection with nature and trying to see how important it was to save our environment and our animals, that happened around fly fishing for sure. When I made my first catch and release, I understood we must have respect.

TSL: Wow, that’s amazing, to be introduced to that at a young age. Well, speaking of a young age, how are your daughters now? Are they still riding off mountain-bike jumps, and how big are those jumps now?

GB: No, now we have a big pump track here in the lodge, and we have a course with little stairs and jumps and everything. They train like two days a week here with the teachers that we have in the school. They’re growing a lot, a lot. They are still good riders. They’re awesome. And we have Gabito, who’s one year and a half.

TSL: He is your new son?

GB: Yeah! He’s using the push bike now.

TSL: I guess they’re taking after their Papa.

GB: Yeah, yeah. I guess so!

TSL: And you had a successful career as a professional mountain biker. How did you get into mountain biking?

GB: Well, I got into mountain biking when I was little, but not racing too much. I used to race a lot of dirt bikes, and I was pretty good. I got in an accident when I was 16 and broke two vertebrate, so I stopped racing dirt bikes, and I say to my mom, “OK, Mom. I’m gonna sell my motorcycles and buy a downhill bike.”

I didn’t race for too many years; I think five years in total between junior category and elite. I like to push a lot. When I do something, I want to do it good. That’s the way for me. I want to be professional in what I do.

It was hard because in Chile, families tend to be super traditional. So, this 18-year-old guy who want to be a professional mountain biker and fly-fishing guide—this was rare. But my mother always supported me. I told her, “Mom, I don’t wanna study. I wanna be a professional.”

“You want to be a professional?” she said. “OK, I’m going to support you. I will not give you money to race, but you must be the best. If you want to go training, I will take you there, but you must be the best.”

I was racing half the year, and the other half I was fly-fish guiding down here in Patagonia.

A big part of my family did not agree with this. But of course, sports give me a lot of things, taught me that nothing was impossible. Sport showed me how to set steps and go over those steps. That was something very important in my life.

TSL: That drive from your sports culture and mountain biking has translated into where you are now with all your ambitions?

GB: Yes. I retired in 2002, as the number one in Chile, but maybe if I hadn’t, I could be in the World Cup. But I was very realistic about that; it was super hard to live on mountain biking in Chile. There was no support, there was nothing.

But I have other things here like guiding, fly fishing, that gave me that connection with nature and that I could live on. And after I retired from mountain biking, I didn’t ride for maybe 10 years.

Then one day, after I was married to Carmen, I said, “OK, I want to stop fly-fish guiding a little bit, and I want to start mountain biking again.” And I saw that where I live in Coyhaique, there was a lot of opportunities to create something with mountain bikes. I had all this experience taking care of the fly-fishing clients, so I used that experience and started to make mountain-bike groups and develop some trails. And that started working. When I first started, everybody looked at me and said, “What are you doing? You have been guiding for 15 years, and now you’re gonna guide mountain biking? There’s nothing here. Are you crazy?”

“Yeah, I’m crazy, but I believe in this.” And now our business is 100 percent about mountain biking. The lodge is focused on mountain biking. We have the bike shop. We have the mountain-bike school. We support the trail-building crews. I realized one thing that I really, really love is mountain biking. And now, I have more support than when I was racing. It’s my passion. Now, I live for mountain biking.

TSL: That’s neat to hear about that evolution in your career and part of that support has been the Patagonia brand. How did that relationship come about?

GB: That relationship started about eight years ago when I was fly fishing. We made a video down south here, with my dog and a really crazy crew of friends. We went exploring where nobody goes, and a big relationship started. Patagonia is a great brand, and it’s so cool that they are not interested in the World Championship but rather people who take care of what we have around us. For me, Patagonia [the brand] has been crucial. It’s awesome. I’m not in the good shape, but I love mountain biking, so they support me. That’s where you understand that they’re thinking about other things. We want to save our planet.

Where I live, I see that there are not too many opportunities for a lot of kids to go and study outside, but I saw the opportunities I have here without being a local. There’s a whole new crew of kids that are mountain biking now. Of course, they wanna be racers, but I tell them, “Hey, man, you could live for this, but it’s not all racing, so racing is not everything. This is a lifestyle, and if you love mountain biking, there’s a lot of ways to live on it. There are so many things beyond racing. It’s awesome, but there’s a lot of sacrifice behind that—a lot.”

TSL: I love that, Gabo. I can relate to that, that dream of being a professional athlete that kids have. And you’re sharing with them new ideas about what you could do with mountain biking and how you could diversify and still hold that as the passion that is your compass for what you’re doing with your life.

That actually gets me into the next question I have for you, about mountain biking in Chile. How would you describe the culture of mountain biking in Chile right now?

GB: I think it’s expanding a lot. It’s becoming a lifestyle. Of course, there’s a lot of racing, but if you go to a mountain-bike race, when it’s over, everybody is with their families, everybody is enjoying together. I think it’s a different way of racing, a mix of racing and lifestyle.

I can see in our business that mountain biking is becoming a lifestyle. A lot of groups, they don’t race, but they have all the same T-shirts, their groups have a name, and they go out together every weekend or three times a week. That’s culture.

We have an amazing, amazing country. We have a lot of mountains, a lot of mountains, and where I live, in Aysén, mountain-bike culture is new. Not more than 10 years.

TSL: Tell me more about where you live, for those who are listening. Tell us about the Aysén region. What is it like?

GB: First, the Aysén region is one of the largest regions in Chile. We have everything. We have from the sea to the border with Argentina, where it’s super dry. We have rain forest. We have ice fields. We have a lot, a lot, a lot of lakes. We have everything in one region. It’s awesome. It’s beautiful.

We are a ways from Santiago—about 1,000 miles [1,600 kilometers] south of Santiago. You could get here on a straight flight that is about two-and-a-half hours. As a region, it’s super new. The city of Coyhaique is maybe 100 years old. It’s hard here, very windy and cold. Living here was not easy in those early years. But Coyhaique has everything. You go east and you have the flat land, which is drier. You go west and you’ve got the rain forest. Mountains are great. We have big forest. The dirt is awesome. We have grip all year.

TSL: I have been fortunate enough to see a little bit of your amazing region, and I love hearing you describe it. I am curious about a lot of the trails you’re building and riding. They’re old resource-extraction roads, maybe even generational Indigenous pathways, and I want to know, how do trails fit into the culture and history of the Aysén region?

GB: Well first, the main activity in the Aysén region for a lot of years, and one of the main activities now, are cows or other farm animals. So, there are a lot of trails. And the locals, when they raise cattle and have to move them to Coyhaique, sometimes it’d take three months getting all those animals to the place where they sell them. All those trails are there in the mountains. Today, they bring a truck and put all the cows in the truck.

We have been making the long process of scouting all—not all, but part—of those trails and trying to clean them up and use them. They have a big history.

Another thing that we have been doing. There was a lot of wood extraction in the mountains, so a lot of places have lots and lots of fire roads, and we have been working on making trails over those fire roads. We have a long ways to go; we’re just starting. I know that we have maybe 10, 20 years more, right? The next generation is going to have a lot of trail, but they’ll still have to work for them. But there are endless possibilities here to make good trail systems—not easily, but they might not have to build from zero.

There are a lot of people that live in the mountains now that take out firewood. In La Gloria (a large, privately owned forested area outside of Coyhaique historically used for firewood cutting), there is one guy who bought a little mountain bike because he sees us every day riding our bikes. So, he decides to buy a bike to carry his chainsaw for cutting. But that’s the first step. Now, he’s riding a mountain bike to go make firewood; maybe in two years, he’ll have more attention for the trails.

TSL: You’re inspiring locals to think about their own lifestyle and incorporate mountain bikes into what they’re doing.

GB: Yes, firewood here is important for a lot of people because they have made their living about that. But those people … they love the mountains. They live in the mountains, so if you could give them another way to conserve and to live in the mountains, I think that’s the key. That’s what I want to work for, how to give value to that. How to show them that maybe instead of cutting the trees, let’s take care the trees. That’s our vision.

TSL: I know one of your passions is growing outdoor recreation as an economic force in your area, maybe into something people will want to do more than collecting firewood or some of the other extractive industries in your area. Tell me, what has motivated that push from you to try to increase outdoor recreation?

GB: Well, first, I want to say we always use our mountain-bike tours to open these places. A lot of the local people may not agree with us because we’re paying the owners of these farms for access. Most of these places, they aren’t open to everybody. The local people don’t understand that my vision is like, OK, let’s go in with the tours first. Let’s show them the mountain bikers can conserve, that they can live with mountain biking and mountain bikers are not so bad. Then the owners agree with us and say, “OK, let’s open it now. Let’s be part of the trail system for the community.”

We are always thinking about opening these places in the future to everyone, but you have to understand that you’re going on a mountain bike into a place where people have never see a mountain bike. So, we don’t want to go in as an invasion; we want to go little by little, and then that man you saw cutting firewood is now riding a mountain bike, and the owner of that big farm now wants to build more trails. Then we’re ready to open it. Because we know that we could handle that.

Sometimes what happens here in Coyhaique is that owners of farm give a space to make some trails, but nobody take cares of them. Most of the places we use, I pay for the access and build the trails—so, I was pretty much paying to use my own trails. And people ask me, “Hey, but how is that your business?”

Well, I know that this is not a business, of course. But I have to do it. This is the way to show the owners that we can make something, because we have to start conservation in all these big private farms that are getting exploited. We have to change those owners, show them how to do conservation. Sometimes to a farmer, conservation sounds like, “Whoa, no, no, no, no. I don’t want that for my farm.” But we can make conservation about sports. We can use other kinds of conservation.

I agree that there are some places where, if there hasn’t been a trail, there doesn’t need to be. I’m not gonna go build a trail in the national park, of course. No, we need those spaces for animals and everything. But we do have a lot of private lands, and those private owners want to make trails. We have to show them that we can be respectful, that we are not going to light their farms on fire, that we respect the other things that they are making inside those farms.

For me, that can be really hard. Sometimes, we build a trail and by afternoon there are 10 cows walking up our trails, so all the work of the day is gone. It’s like, “OK, tomorrow I’m gonna make it again, but please, could you take care about the cows, man?” But that’s part of making this grow.

TSL: What motivates you to do that, Gabo? That sounds like a lot of work to convince farmers and ranchers and private landholders to get on board with your vision. How are you motivated to do that?

GB: One thing that was really cool, in La Gloria, most of the people that live there didn’t know about the highest part of the farm—it’s like the top of the mountain. When they saw us riding bikes up there, I say, “Yeah, I build a trail to the top.” “What?!” “Yes! I’m going to show you the top of your mountain. You have never been there?!”

When we open these kinds of spaces, the owners are happy. They know their place now, what they have and what they could do. When they’re walking a beautiful trail on their land, they are like, “Wow, this is beautiful.” “Yeah, this didn’t exist. We made it.” They start to see the potential that they have, and they can imagine the future with this.

We got one project I have been pushing for like five, six years, that is La Gloria. The owner is a great, great, great man called the “Capitán.” Of course, Capitán works his farm with all this crew that cuts the woods, but he gave us the opportunity to make these trails and to start developing this farm. It’s super big, and it’s close to a little town called Villa Ortega, a super little town. Now, we’re figuring out how we connect this town with all these places we want to protect. But we don’t want to go there and say, “We’re gonna do all this conservation and you can’t cut any more firewood here.” No, no, no, no. Let’s see how we could all share together because I know that in another 10 years, we’re gonna have more people maintaining trails than taking out woods.

If you don’t try it, you never know. Sometimes you win, sometimes you don’t.

TSL: Spoken like a true visionary. In parts of the US—including where I live right now in Rico, Colorado—outdoor recreation has become so popular that it’s become its own sort of extractive industry, where crowds damaging sensitive habitats and overwhelming local communities is a common trend we’re seeing. Do you fear outdoor recreation could become something similar for communities and environments in the Aysén region, and if so, in what ways do you think it could be managed?

GB: One hundred percent. I think outdoor recreation could be a big thing, big, big because we have everything. And I think the way to do that is working in these little towns and with kids. We’re losing localism. Kids, when they turn 15, 18-years-old, most don’t have the opportunity to go study. But nobody has shown them all the other things they have around. They have the mountains. I didn’t study anything. I live on this, and I am not a local. I don’t have a history here. They have everything, but we need to figure out how we give them the tools to realize that there is an opportunity because I know that not every one of those kids want to work on the farm.

And I’m not saying about that they’re going to lose their gaucho [South American term for “cowboy”] culture. No. They’re still gonna be gauchos, but in a different way. They’re never going to lose that culture. But if they don’t want to build fences, maybe they could hop over a mountain bike and guide or over a horse or walking or hiking or fly fishing. Why not? Why not? We need that. Give them the opportunity to know the sport, maybe know another language. But they have everything else. They have history. They are gauchos, and they’re gonna be gauchos over a mountain bike or over a snowboard.

I think that’s how we make that localism stay here and not go outside the region. Because it’s super easy for them go work on a fish farm or going to the mines. That’s the easier way. Or they come down to the city and we’ve lost them. We’ve lost a lot. It’s hard, but we need the spaces for them to do that.

I know that a trail system is more than having fun over the bike. That’s my view. I love to ride good trails, but I know that a trail is more than fun.

TSL: So, you are saying that the generations to come could manage these trails? And that staying there and having the passion for building those trails, or being guides in the area, and loving their place and the lands that they come from is going to help create education for everybody? And right now, you’re just trying to get your feet underneath you with trail networks in general, because there’s not much. Is that right?

GB: Yes, and that’s it. I think that’s what we need. I started realizing that, when I was a fishing guide, I looked around and thought, “There isn’t a new generation of guides. What are we doing wrong?”

We start doing this with all our businesses, in the tour company, then the store, then little things that help us bring all these together and try to support the trail builders. Now, we are trying to build a foundation working with these local communities. And more than focusing on Coyhaique city, I want to focus in little communities. That is where we have to go. I don’t want to say that in Coyhaique there’s no culture. Yeah, there’s a lot of culture. But it’s a big city. You have more opportunities.

In those little towns … that’s where you live in the real Patagonia.

TSL: That’s a lot of hard work, Gabo. I’m sure this past year has been a little bit crazy for you, as it has been for most of us. COVID-19 has disrupted life around the world, and we even had a delay in this interview because of the COVID-19 surge in Coyhaique. Can you tell me how the Aysén region is doing now?

GB: Well, this region receives a lot of tourists. So, all this season has been really, really hard. We didn’t receive any bike trips since March of last year. We’ve been through one year without working. But I’m happy that we just have the store, the bike shop. When we started the bike shop, we had nothing. I said, “OK, how are we gonna make it?”

The bike shop is doing really well now. We don’t have too many bikes, but we’re selling bikes, and it gives us a little bit to continue supporting all our team and that was super important for us.

We know that this is gonna end. I don’t know when, but I hope the next season is gonna be more like normal. A lot of people want to come, that’s true, and you could see that. We have to wait, be patient. There’s no option, just be patient.

Sometimes, I said, “OK, maybe I should stop.” No, I could not stop, I could not stop. This is for new generations, and one day all my trails are gonna be open for everyone. But somebody has to do it, and you cannot go to a place that’s not yours and open a trail for everyone and then make a mess. That doesn’t work. And this is so new here, that’s why. So, we have to take care about that.

I can see that because like 20 years ago, when we were starting into fly-fishing guiding, you could go everywhere. But then some guys start jumping inside the gates without permission, and some places were closed. Then that great lake when you go fishing, now you cannot get in. So, we have to make things right.

I know that all the trails I have been working on and paying for, I will never get that money back. I know that. But I’m so happy when I see that they can make a living doing that, and if we could give that little piece of help—that’s for all of us.

TSL: I admire that so much about you, Gabo. In seeing the potential for being able to create more sustainable jobs in trail building. And having trail building be valued because it’s ultimately a way for people to get into the outdoors and learn about nature and learn about the places that they live. And I hear you say how challenging it is and luckily you have that professional mountain biker in you, that won’t give up. And this has been a wonderful conversation. Is there anything more that you’d like to add?

GB: I just do this because I love it. It’s not for ego. It’s not because I wanna be recognized. No, this is for everybody. I want to make something for the region. It doesn’t matter if my name is there or not. I love this. It’s my passion, it’s my life, it’s my lifestyle. And I hope I can push for that a lot of years more and try to change people minds to see that there are other opportunities. We live in an awesome place, and all Chile—it’s great.

It’s great to see how you motivate some people. For me, it’s so important to have Edecio and and Juan and the other trail builders. And maybe we are a little community here now, but we are real community. We are living doing what we really love, and that is mountain biking.

And this is for everybody. Trails for everyone, that’s it.

By Teal Stetson-Lee, Patagonia.com

For more information and details : https://www.patagonia.com/stories/trails-for-everybody/story-100702.html

Extreme adventure at the edge of the word: sail and ski in Norway

There are few more thrilling places to ski tour than the Lyngen Alps, a 55-mile chain of peaks that punctuates Norway’s fragmented northerly fringes.

“Sometimes you have to do things you’ve never done to get to places you’ve never been.” These are the words of wisdom offered by our mountain guide, Espen Minde, as we take a break from climbing 1,000 metres on skis up an unnamed peak in Norway’s Lyngen Alps. Something, indeed, I’d never done before. We’re also climbing straight into a blizzard. Normally, in conditions like these, I’d have turned back or maybe not even set off in the first place. But Espen, being a Norwegian mountain guide, isn’t put off by driving snow, howling winds and zero visibility. And as our group — comprising six other skiers — has every confidence in Espen’s years of experience touring these wild, often unnamed mountains, we plough on.

Ski touring in the Lyngen Alps isn’t always like this, of course. Aboard the Arctic Eagle catamaran, the comfy floating accommodation for our ski and sail trip around Norway’s northeastern shores, we’ve seen all weathers. On the first day, having sailed for three hours from its base in Tromsø, Arctic Eagle anchored off the coast of Vanna island, afternoon sunlight glinting on the waters of the fjord as our captain, Håkon, ferried us to the rocky shoreline.

Once on dry land, we start our 1,031-metre ascent of Mount Vanntinden. The snowbound peaks of the Lyngen Alps bear down on us from all quarters, rising majestically up into a baby-blue sky. There’s not a soul to be seen and not a sound to be heard other than the gentle lapping of sea against shore.

Espen leads us at a gentle pace, with breaks to take in the view. It’s late April and we’re well north of the Arctic Circle so we have plenty of daylight. The views as we ascend become more spellbinding, the slowly sinking sun casting an increasingly golden glow across mountains and sea. By the time we reach the summit, the sun is just above the horizon and we’re on top of the world in every sense. It’s high fives all round, a fast round of photos, then we need to get moving to get back to the boat before dark.

We remove the climbing skins from the base of our skis (the sheathes that allow you to ascend without constantly slipping backwards), flip our ski touring bindings to ‘descend’ mode, don a couple of warm layers, tighten up rucksack straps, clip into our skis again and set off downhill.

We’re able to spread out and enjoy big, swooping turns across huge snowfields almost all the way back down to the fjord, skiing into the setting sun, a glorious landscape of deserted mountains and dark-blue sea spread before us. Whoops and hollers of excitement are inevitable and why not? There’s no one else around.

Back aboard Arctic Eagle, everyone is ready for a beer, but not before one unavoidable Arctic ritual: a quick dip in the icy Norwegian Sea. With the water temperature at around 5C, no one stays in for long. Warm and buzzing after a hot shower, we gather in the catamaran’s galley around the large table to enjoy freshly caught cod and cold beers, before Captain Håkon, who’s sailing us east to anchor off the coast of Arnøya island for the night, shouts: “Quick! Come up on deck!”

The Northern Lights are doing their thing in the starlit skies above. A relatively muted display of pale-green swirling waves passing over us, but it’s a winning finale to the perfect day. Not every day is so blessed, of course. This is Arctic Norway and the only predictable thing about the weather is its unpredictability, but over the course of the trip we get to ski amid the most incredible scenery, in everything from sunshine to mist, sleet and snow. Eventually, six days after setting sail from Tromsø, Arctic Eagle returns us to its home port. Exhausted, sunburnt, weather battered and happy, we step ashore and say a sad farewell to Captain Håkon and Espen, safe in the knowledge that it’s absolutely worth doing things you’ve never done to get to places you’ve never been.

By Alf Anderson, National Geographic

For more information and details : https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/extreme-adventure-sail-ski-in-norway